When I tell people I study social media, politics and social movements, I often get a version of the question: “But there were protests before Facebook?”

Sure, I say, but how did people hear about it? Word-of-mouth is, of course, one way but [in the modern era] [and especially in repressive settings] it’s almost never never fast enough to spread protest of news quickly enough–remember, a political protest is a strategic game with multiple actors including a state which often wants to shut them down. Too slow diffusion of information, and your people will get arrested faster than they can show up at all. History of modern revolutions is always mixed up with the history and the structure of the communicative infrastructure of technology.***

That is why the speed of the initial response curve is crucial to whether a protest will survive or not. In Egypt, activists protested for many years on January 25 before 2011. But there were too few of them (100-150 per year) to sustain against the repression. On 2011, the initial day, there were about 5000-10000 people in Tahrir. It was too many, and it wasn’t the usual suspects (“It wasn’t just your usual activist friends, it was your Facebook friends”, an activist told me explaining how he knew it was different that time) and the movement was able to roll out from there. [Added: See footnote. I’m clarifying one aspect of a complex story. This is, of course, not the whole story!]

Turkey, my home country, is known for big demonstrations. After the Arab Spring, there were demonstrations of about a million people in Diyarbakir (a predominantly Kurdish region) and people asked me if this was Turkish spring. I laughed. Diyarbakır can have a million people to have party to sneeze together. The Kurdish opposition is well-organized and has always been able to bring large numbers to streets. May Day celebrations in Taksim, Turkey are legendary (they alternate between lethal and joyous and are often quite large). But they are also always organized by trade-unions and political parties.

Turkey has has a variety of large demonstrations over the years. Not a single large, widespread spontaneous one, though.

The last somewhat organic, widespread demonstrations I can remember in the 1980, post-coup era are the “1989 Spring” workers’ strikes and actions which were widespread and which culminated in the Zonguldak mine workers strike. And those were also somewhat- to completely-led by the trade unions.

Pretty much every other large, impactful political gathering in Turkey I know of has been organized by a traditional institutions.

So, Turkey has been a NAACP country, not Tahrir.

That is, until yesterday.

So, let’s get some of the Tahrir/Taksim comparisons out of the way. Turkey’s government, increasingly authoritarian or not, is duly elected and fairly popular. They have been quite successful in a number of arenas. They were elected for the third time, democratically, in 2011. The economy has been doing relatively well amidst global recession, though it has slowed a bit recently and there are signs of worrisome bubbles. So, Turkey is not ruled by a Mubarak.

But it’s also not Sweden. The government has been displaying an increasingly tone-deaf, majoritarian-authoritarian tendency in that they are plowing through with divisive projects. (I should add that the opposition parties are spectacularly incompetent and should share any blame that goes around).

The government has also revolutionized Turkey’s government” services through the expansion of a spectacular level of e-government–which has greatly eased many people’s lives as bureaucracy is a major quality of life issue in countries like Turkey. This, in turn, has altered power relations between civic servants (who form the majority of the secular middle-class which does not vote for AKP) and the mass of citizens (many of whom do vote for AKP).

However, the expansion of e-government has also enabled and been accompanied by expansion of state surveillance. [So, in many ways Turkey is both more free and less free].

There has also been great pressure on media to self-censure (to be honest, most Turkish mainstream media is not lining up for press courage awards, either, so most have been compliant and cowardly to the degree that CNN Turkey was showing cooking shows while CNN international was showing the protests in Turkey as a major news story yesterday). Further, the government has been moving to legally “mandate” lifestyle choices regarding alcohol, Internet content, etc. to create obligatory behaviors rather than recognizing that there are large swaths of the country that does not agree with its views on what one should drink or watch (ironically, also among its own voters.)

So, what’s the underling structure of the protests? It’s an increasingly tone-deaf, majority government who is relatively popular but is pursuing unpopular, divisive projects; an incompetent opposition; a cowardly, compliant mass media scene PLUS widespread, common use of social media.

In Turkey, especially in large cities, almost everyone has at least one cell phone, and many of them are Internet enabled. (You must provide your citizen ID number to get one which also means that the surveillance capacity is also broad although the amount of data means that the surveillance is likely targeted rather than just broad and random). Facebook is very common, with more than 30 million users. (It’s in the top ten worldwide). About 16% of the Interet population also uses Twitter and, as in here, Twitter is very important exactly because who those 16% are. (In fact, probably more important because it is not everyone and creates a somewhat more exclusive space though that is eroding).

One area that has been creating increasing tension between the Turkish government and many citizens in Istanbul has been the urban renewal projects undertaken by AKP. Some, for sure, are popular like the “metrobus” that zips between the two continents in a dedicated lane, bypassing the torturous traffic jams. Others, like the “renewal” of the wonderful, unique tapestry of Tarlabaşı near Taksim, home to Roma, transexuals, urban poor and other misfits, by bulldozing this area to throw up soulless, concrete and glass structures to be built and sold, helpfully, by the prime-minister’s son-in-law, are largely unpopular ,both among the people who live in these areas or who inhabit the beautiful, vibrant areas around Taksim, Beyoglu, Cihangir.

So, it is not a coincidence that the latest incident was sparked by attempts to resist renewal of the “Gezi park” area of Taksim which has the last teeny-tiny bit of green in a very concrete, overbuilt part of Istanbul, historic Taksim. There was some long and complicated back-and-forth about this which ended with the government announcing that all or parts of the park might be replaced with a … shopping mall.

(Disclosure, I personally think most shopping malls are the secret 11th circle of hell, as described in the lost copy of the Dante’s Inferno that will be revealed in Don Brown’s next bestseller book!)

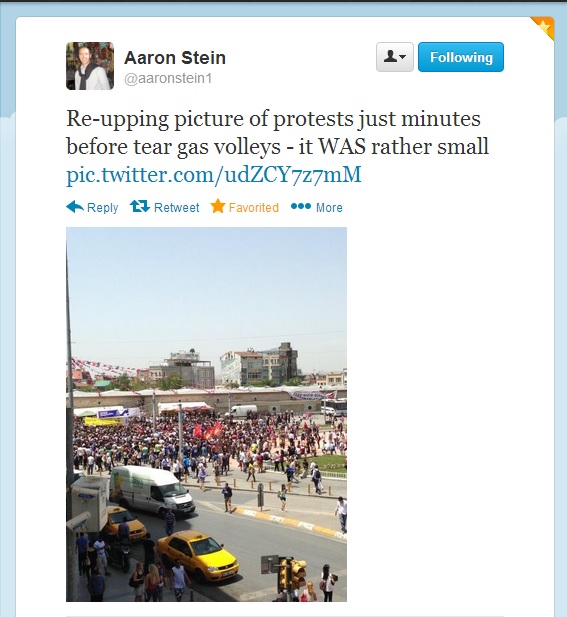

So, when a small –I repeat a very small, especially for Turkey– group of people tried to resist the bulldozers uprooting of the trees in Gezi to begin the construction, I did not think that much of it.

Here’s how small the protests were, from Aaron Stein’s tweet stream.

What happened next was a horrific, disproportionate police response which included a lot of tear gas and beating up of protesters. However, I should note that this, too is not unprecedented. Not at all. This Reuters image, which rang around the world, makes the situation fairly clear.

Then, the incompetent and cowardly media coverage started acting as usual–which meant a general blackout of crucial news. This, too, is not unprecedented. Many major news events, recently, have been broken on Twitter including the accidental bombing of Kurdish smugglers in Roboski (Uludere in Turkish) which killed 34 civilians, including many minors. That story was denied and ignored by mainstream TV channels while the journalists knew something had happened. Finally, one of them, Serdar Akinan, was unable to suppress his own journalist instincts and bought his own plane ticket and ran to the region. His poignant photos of mass lines of coffins, published on Twitter, broke the story and created the biggest political crisis for the government. Serdar, unfortunately, got fired from his job as a journalist.

Here’s Serdar’s Twitter pictures breaking the news about the biggest political scandal in Turkey in years, in face of mass media silence on the topic. (Twitter search failing me in finding his original tweet but here he is telling people he is going to the area, by himself, as the silence about the bombings continues on media).

It was after the Gezi protesters were met with the usual combination of tear-gas and media silence something interesting started happening. The news of the protests started circulating around social media, especially on Twitter and Facebook. I follow a sizable number of people in Turkey and my Twitter friends include AKP supporters as well as media and academics. Everyone was aghast at the idea that a small number of young people, trying to protect trees, were being treated so brutally. Also, the government, which usually tends to get ahead of such events by having the prime minister address incidents, seemingly decided to ignore this round. They probably thought it was too few, too little, too environmental, too marginal.

On that, it seems they were wrong. Soon after, I started watching hashtags pop-up on Twitter, and established Twitter personas –ranging from media stars to political accounts– start sharing information about solidarity gatherings in other cities, and other neighborhoods in Istanbul. Around 3am, I had pictures from many major neighborhoods in Turkey –Kadıköy, Bakırköy, Beşiktaş, Avcılar, etc– showing thousands of people on the streets, not really knowing what to do, but wanting to do something. There was a lot of banging of pots, flags, and slogans. There were also solidarity protests in Izmit, Adana, Izmir, Ankara, Konya, Afyon, Edirne,Mersin, Trabzon, Antalya, Eskişehir, Aydın and growing.

So, as far as I can remember, these are the first protests in Turkey in the post-80 coup era that are less like NAACP-organized civil rights protests, and more like social-media fueled Tahrir protests. (Just so people don’t get confused, there are significant differences between Egypt 2011 and Turkey starting with the fact that AKP is a duly elected, relatively popular government that has been growing tone-deaf and authoritarian/majoritarian).

So, is there a social-media style of protest? I think we have enough examples now to say there seems to be, and here are some of their common elements. (Examples include Egypt and Tunisia, M15 in Spain, Occupy, Gezi in Turkey, Greece, etc).

1- Lack of organized, institutional leadership. This also makes it hard for anyone to “sell out” the movement because nobody can negotiate on behalf of it. (For hilarious versions, read Wael Ghonim’s version of how Mubarak officials tried to convince him to call of the protests in return for concessions as he tried to explain that he had no such power!)

On the other hand, this means that the movement cannot negotiate gains either because.. Well, because it cannot negotiate.

2- A feeling of lack of institutional outlet. In the case of Egypt, this was because elections were rigged and politics banned. In Turkey, media has been cowered and opposition parties are spectacularly incompetent. In Occupy in US, there was a feeling that the government and the media are at the hands of the moneyed interests and corrupt.

3- Non-activist participation. I think this is crucial. Most previous big demonstrations in Turkey are attended by people who have attended demonstrations before. Tahrir protests 2011, Tunisia December 2010, Gezi 2013 drew out large numbers of non-activists.

4- Breaking of pluralistic ignorance. I have made this argument before but revolutions, political upheavals, and large movements are often result of breaking of “pluralistic ignorance”–ie the idea that you are the only one, or one of few, with a view. Street demonstrations, in that regard, are a form of social media in that they are powerful to the degree that allow citizens to signal a plurality to their fellow citizens, and help break pluralist ignorance. (Hence, the point isn’t whether the signalling mechanism is digital or not, but whether how visible and social it is).

5-Organized around a “no” not a “go.” Existing social media structures allow for easier collective action around shared grievances to *stop* or *oppose* something (downfall of Mubarak, stopping a government’s overreach, etc) rather than strategic action geared towards obtaining political power. This is probably the single biggest weaknesses of these movements and the reason why they don’t make as much historical impact as their size and power would suggest in historical comparison. However, in the end, politics happens where politics happens and staying out or being unable to join results in a tapering, whimpering out effect as the movement slowly dissipates as it runs out of tactical moves and goas.

6-External Attention. Social media allows for bypassing domestic choke-points of censorship and reach for global attention. This was crucial in the Arab Spring (and we know many people tweeting about it were outside the region which makes Twitter more powerful in its effects, not less.

Here’s CNN International showing Turkey protests while CNN Turkey shows a cooking show. (Image widely circulated on social media):

Through social media, protesters learned that the whole world, or at least some portions of it, was indeed watching. Since protests are as much about signaling more than they are about force (as protesters are almost never more powerful than state security forces), this is a crucial dynamics.

7- Social Media as Structuring the Narrative. Here and in other protests, we saw that social media allows a crowd-sourced, participatory, but also often social-media savvy activist-led structuring of the meta-narrative of what is happening, and what shape the collective grievances should take. Stories we tell about politics are incredibly important in shaping that very politics and social media has opened a new and complicated novel path in which meta-narratives about political actions emerge and coalesce.

8-Not Easily Steerable Towards Strategic Political Action. This we have seen again and again and is related to point number 5. Social-media fueled collective action lacks the affordances of politics an institutional arrangement –political party, NGO, etc– can provide.

Where is this going? I can’t offer predictions but I do emphasize that this is not going to topple the Turkish government by itself. This is not Tahrir, 2011, but it is an interesting inflection point among the frustrated but powerful segments of the Turkish society who believe that the current government has decided to run roughshod over them and cannot find efficacious outlets for their opposition.

[added] Here’s a striking example of what media cowardice and self-censorship looks like. New York Times covered the Turkey protests on the front page of its online site. Sabah, a major newspaper in Turkey, did not put one of the biggest protests in Turkey on its front page at all.

What happens next depends on many factors including the government response and the depth of the feeling among the Gezi protesters. I doubt, however, that this is the last social-media fueled protest we have seen.

OBLIGATORY FOOTNOTE:

*** It should be needless to say at this point but just so someone who thinks this is somehow a profound comment doesn’t feel like they have to point it out fifty times in the comments section: OF COURSE REVOLUTIONS ARE MULTI-CAUSAL, COMPLEX EVENTS AND THE COMMUNICATION INFRASTRUCTURE DOES NOT CAUSE THE UNDERLYING GRIEVANCES BUT RATHER IT HELPS STRUCTURE WHAT KIND OF, IF ANY, COLLECTIVE ACTION IS ORGANIZED AROUND THE GRIEVANCES.

(Sorry for the all-caps but I spent the 2011 “Arab Spring” year having to respond to people who felt compelled to keep saying political uprisings are about social, economic and cultural grievances as if there were actual serious people who claimed otherwise–and as if that fact meant the communicative infrastructure was irrelevant which is either the view of a naive person who has never lived under a censorship regime where it becomes blindingly obvious why communication infrastructure matters–yes, all the way back to 1848 and even the French revolution as those stories are intertwined with the development of print, telegraph, railroads (which carry news and newspapers), etc.)

**** (Also, I wrote this very fast in an otherwise very busy week. I will correct typos(!), update links, as I get a chance!) This is a “fast and dirty” analysis, not meant to be comprehensive, include every factor, does not list every misstep by the government or by the protesters, nor does it provide the exhaustive or complete list of every factor!

[Final Note: This was a hastily written post but I stand by the analysis, if not the clunky writing. 🙂 Those asking permission to translate. Thank you. Go ahead, just drop me a line and a link back here so I know about it.

Existing translations I know of:

Italian: http://www.valigiablu.it/proteste-e-social-media-unanalisi-da-jan25-a-geziparki/

Let me know if there are others.]

Zeynep, this is an excellent and timely analysis that I would like to post on our globally-oriented Web site. Let me know if you wish to recast it as an article or simply have me highlight the piece and add a hyperlink on the site.

Ne ise, esim ve ben 2 senedir baris gonulluleri olarak Turkiye’de oturup calistik 1965-1967 arasinda.

Well done.

Cheers,

Warren

I agree with a lot of this, and it is absolutely important to try to understand the role played by communications technologies in every part of the social structure.

But, especially given your particular discipline, I’m puzzled by parts of your first paragraph. You write this: “‘But there were protests before Facebook.’ Sure, I say, but how did people hear about it? Word-of-mouth is, of course, one way but it’s almost never fast enough.” The third sentence doesn’t seem to answer the question asked in the second and implied by the first. The pre-Facebook protests *did* happen; they *were* effective (sometimes more effective and longer-lasting than recent ones have been); whatever communication happened, then, *was* fast enough to enable protest.

I mention your discipline because this does seem to me perched on a set of empirical claims about how protest-based communication has taken place in the contexts of a variety of different communications technologies. In order to understand what is special or new about social media protest communication, we need to have a firmer grasp on how that communication worked in other technological contexts. In part, your answer to the questions depend on claims about the speed of communication, and the success of pre-Facebook protests at least suggests that communicative speed itself may not be critical to the effectiveness of protests.

When I read this section about speed I took it to mean that the speed of spreading information needs to be faster now than before, which is where social media comes in as an interesting tool.

Sure, there were protests before Facebook, when information didn’t travel so fast, that were successful. But in those days governments and authorities were also slower in mobilising, locating and suppressing action.

Now, when everyone has this technology, communication needs to spread even faster.

Pingback: #occupygezi: la respuesta popular a la arrogancia de Erdogan | GUERRA ETERNA

Zeynep, can you PLEASE do at least a small blogpost about HOW the social protests are organized.

How does a decision to exit the street at the same time become ingrained in the courteousness of so many people?

Somebody would go out at 10AM, other at 10PM, so what is the exact mechanism that drives people to exit to the street (not that cause, but the trigger that says, go out at 10pm).

Are there anonimous(or non anonimous) calls to exit at a particular time and stay outside, do people just flock to the area to defend the park, or what is it?

It’s obvous to me now that it’s geographical, that that’s a key ingredient, that people know where to go.

But please write a bit about timings, what exatcly is twitted/shared on facebook that calls people to go outside if anything is?

Thank you very much.

Pingback: #occupygezi

Great piece. Forwarding to the ghost of Chuck Tilly.

Thanks for this interesting article, I have been following this since yesterday ONLY because I made a facebook finally and because I subcribed to the page World Riots 24/7 which was one of the first to start posting images at least on facebook, not long after this started. I keep reading on twitter that twitter and facebook are down in Turkey now, don’t know if that is true, lots of turkish tweets coming through the feed but don’t know the location of them so it could be expats…great analysis. I am heartened by all of this, someone just posted an aerial of the protestors in the square and it shows just how small that patch of green is in that concrete jungle. Only negative press I have read has been commentors on the Financial Times article saying that Turkey’s neighbors will take advantage of this situation by arming the soon to be called ‘rebels’ and turn turkey into yet another islamic state. I really hope there is no credence to this, and I hope the violence stops though people on twitter are saying things in Ankara are getting bloody. I guess all the reference to social media proves your point, before all of this there was only Cspan which I would stay glued to.

I believe the idea is that word-of-mouth was fast enough *then*, but that it’s not fast enough in the modern era. The requirements for speed are relative, not absolute.

Zeynep

How serendipitous. I had just finished putting together a lecture and discussion covering Gladwell, Shirky and Castells re insurgent movements, democracy, and the power of social media and then called up my Reader and found this essay that probes those very same issues. I am sending off to my students as a very fresh example of the topic. I especially like the contrasting pages and screens.

I find that this is one of the clearest and most interesting analysis I’ve read so far!

Thanks!

Pingback: Turkey is not Egypt, you lazy fool | Jillian C. York

Great and incisive post, sağol!

Very interesting article! Given the importance placed on social media, can anyone confirm/deny claims that social media is now being blocked in Turkey?

Your wording implies that Turkey sits in between Mubarak’s Egypt and Sweden on a democratic scale. That is misleading. Turkey is ridiculously closer to the Mubarak model.

Nice article with accurate sightings. Once more, this is a proof that technology will change social behaviors, customs, traditions, and everything we got used to. I wish cellphones were invented 100 years ago. too late too little.

Pingback: Lately in Istanbul: Istanbul erupts (the best things I’ve read) | Green and Ginger

Pingback: Select-Av » Civil unrest, Istanbul

Great analysis for the rather uninformed reader that I am – thanks a lot!

I absolutetly agree, though, with what David said – and it might be crucial to your field: “The pre-Facebook protests *did* happen; they *were* effective (sometimes more effective and longer-lasting than recent ones have been)” –

There can be no doubt about that – for recent examples please think of the social movements of the 80th and early 90th in Europe, antinuclear, feminist, squatters, ecology, gay…)

Its certainly true that social media/virtual media are great for organising large numbers of non-activists spontaneously. But are they not, up to now, very bad in creating stable organisations, continuity or shared, binding strategies?

Why is that so?

My quick and dirty Hypotheses in a sentence:

Sociel media have “educated” their “custumers” long time before any protests can start – and in a way that makes their very protests rather ineffective in the long run!

F.E.

“educated” into beleiving, that leaving messages and expressing opinions is what count’s – not really reaching agreements, compromising, inter-acting across partisan-lines or just lines of “opinion”.

.. educated into the experience that one can “act” from a computer – and that one does not necessarily need to “inter-act”, non-virtually, for anything one want’s or needs.

What is it, actually, that you “do” via the inter-net: Read/Buy/express yourself – thats definitely not enough for an uprising to have lasting impact 😉

….

So basically I’m suggesting to do much more research: And not mainly on the advantages and possibilties of sm – but also, on what its long-term consequences might be for everyday cultural beliefs and attitudes etc. with a focus on impacts on chances for effective collective long-term-organisation…

And please don’t forget, that the two main uses of the respective technologies are buying and selling.

One of the best examples for the kind of unwanted consequences created when politics are translated into “social” communication without any awarness of those cultural factors:

The rise and very steep fall of Germany’s Piraten-Party.

PP was and still is a transparancy and democratisation movement established mainly by the first internet-Generation. It received tons of sympathy by the general public – yet it managed to ruin it’s reputation within months – and through false expectations:

Certain expectiations/Attitudes seem to have been shared – and completely underestimated, to my mind – by the very PP-generation grown up with the givenness of the net. It’s enthusisatic political Project basically created – uge chaos! It seems to me this was the kind of chaos supported by the very media-habits and attitudes that had been, in the eyes of the party’s members/acivists, destined to provide total democratisation…Shortly the problem was that everybody is commenting everything, and everybody – without any chance to reach an end, not to speak about consensus – not to speak of coordinated action.

Please feel free to contact me – but don’t publish any Adresses.

Alatheia, thanks for deepening Zeynep’s journalism, which indeed already offers a quite penetrating analysis in itself. Let me add a comment on what Zeynep calls “Lack of organized, institutional leadership”:

In the end (which may come sooner than expected) , a movement that has no leadership cannot win, because victory necessitates negotiations. As an example of the political questions that will have to be negotiated: Will Turkey remain a member state of NATO if the the movement succeeds in toppling the Erdogan government?

malaysian protests use #blackout505 and #black505 for the demonstrations against fraud and rigged recent election , the ‘death of democracy’ . About 150,000 people rallied in Kelana Jaya near Kuala Lumpur 3 days after the election results came out.

Pingback: Turkey’s #geziparki And Similarities with Other Social Media-Driven Protests. | Blog Square

A good analysis; which is not surprising since you are already an accomplished scholar in the field and have the advantage of Turkey being your home country. However, there are two major weak points:

1. The success of AKP government is overrated. For one thing, absolute progress doesn’t mean much. Relative to other countries’ Turkey has been getting worse in many areas (e.g., innovation and e-government that you praised – if you wish I can provide the reports which you can easily find in Google). Second, growth or balanced budget are not the sole indicators of the economy; thus, “The economy has been doing relatively well amidst global recession…” is not quite right. Again, if you check HDI and many other indices, Turkey is far behind even relative to “economically bankrupted” Greece. It’s just that (a) Turkish people gets easily content with what they have as long as there is no major crisis like the one in 2001; (b) news media loves to create a false grandiose, to flatter the ego of people.

2. You mention the cowardice of the Turkish media, but you seem to have greatly underestimated the incompetence and flattery attitude (toward both public ego and ruling party) of the media. Just one example. I’m sure you know that after WCIT in Dubai, there were mounting criticisms that, because ICANN is in LA, governance of the Internet is too America centric. Upon which ICANN made a tactical decision to open offices in Istanbul and Singapure. The headlines of our major newspapers: “Istanbul became the capital of the Internet” “Center of Internet” “Boss of the Internet”… Each and every day, people read how wonderful we are in every area; which suits people’s ego as well as the ruling party!

These two facts (especially the second one) have profound affect on your other rather exaggarated statements: (1) “opposition parties are spectacularly incompetent” (if “spectacularly” is replaced by “somewhat” then it’ll reflect the truth – I can share numerous cases where I personally felt totally helpless and hopeless with this media and decided not to run for a third term as MP in the 2011 elections); (2) the election successes of AKP. With this media and RTE’s religious manipulations, these successes look more than what they are in reality. If you answer just one question, both of these two exaggarations will become more clear:

If, as you wrote, the AKP government “…have been quite successful in a number of arenas” and if the main opposition party is “spectacularly incompetent” then why the PM Erdoğan avoided a national TV debate against Baykal (the leader of the main oppositon then) before 2007 elections, and against Kılıçdaroğlu before 2011 elections? (When, at the time on TV and other platforms I raised this question to the representative of the ruling party, the answer is “well, they are not worth to have a debate” – most ludicrous response, considering that Erdoğan is most every day attacks the main opposition leader)

Otherwise, on the role of social networks and analysis of Gezi movement your analysis is very thorough and useful. Especially, two facts are well captured: (1) these protests are much different from the traditional ones organized by a political party or other organizations; (2) the issue is not only “few trees” in Gezi park nor it is only regarding secular concerns; but it is against dictatorial ruling style of the PM Erdogan.

Nevertheless, I am puzzled why the fact that Erdogan is elected democratically looms so heavily in yours and many other analyses. Didn’t Hitler? Isn’t Ahmedinejad? Putin?

Considering the fact that I wrote the above posting at around 5 AM, after a very wearing day, I hope the reader will overlook the mistakes.

No, Osman, Hitler was never democratically elected. He was appointed to the Chancellorship, whence he destroyed the remainders of democracy. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_presidential_election,_1932) Ahmedinijad? Putin? Democratically elected? Please. No. (The OSCE said, “um, nope.” — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_presidential_election,_2012)

I like your reminder to would-be critics that of course social protests are not caused by new media, and that *nobody said they were*. To me one difficult empirical question, as always, is what part, if any, did different (sets of) media technologies play at different stages of the protest. See http://www.academia.edu/3521160/Mobile_ensembles_The_uses_of_mobile_phones_for_social_protest_by_Spains_indignados

Having worked on the social media front during the recent protests in Delhi, I’m quite convinced that social media does have a lot of role to play in such protests/uprisings. What I find very interesting in this analysis is the similarities in certain roles that social media plays – like structuring the narrative.

Thanks for the post.

Beautiful article, thanks to the speed in reacting, thanks for the quality of the analysis. I also found your paper through scial media (a friend on FB). Thanks again.

Pingback: Sunday! Sunday! Sunday! | Gerry Canavan

Pingback: herrhorn.com

I just wanted to thank you for this post. I have read quote a few analyses on the relationship between protests and social media in recent years. This one is definitely one of the best, mostly because it’s so nuanced and realistic about social media’s strengths and limitations.

Pingback: I social media e la protesta in Turchia » Chiusi nella rete - Blog - Repubblica.it

Pingback: People like you and me (#OccupyGezi #Taksim #DirenGeziParki), Istanbul

Pingback: LabourNet Germany: Treffpunkt für Ungehorsame, mit und ohne Job, basisnah, gesellschaftskritisch » Kochtopfdemonstrationen. Und eine Bedrohung namens Twitter…

Pingback: LabourNet Germany: Treffpunkt für Ungehorsame, mit und ohne Job, basisnah, gesellschaftskritisch » Landesweite Proteste gegen die türkische Regierung

Super great analysis zeynep, You had highlighted the ups and down of the government, the media, and social media.

I have to to share, I have no option but to share this great piece of informative analysis. It is my obligation as a concerned citizen of the world.

I share under the free information act, my blog is for information purposes only. There is no money involve, but the desire to keep the world informed. To raise awareness of our reality.

Thanks for the great job.

Pingback: Better late than never: What is #Occupy Gezi and what does it promise (now)? | You are what you read

Pingback: #Occupygezi e le proteste in stile social network » Punto Nave - Blog

Pingback: TeleradioNews ♥ non solo notizie da caiazzo & dintorni » #OccupyGezi, la protesta in Turchia è anche social

Pingback: Add Tear Gas and Stir -- Images of Police Brutality Fuel Anger in Turkey - NYTimes.com

Terrific observations, Zaynep; as I race to finish my book, “Swarms: The Rise of the Digital Anti-Establishment” it is very clear that the rise of strategic “adhocracy” networks are creating new infrastructures of accountability which, for better or worse, are becoming extremely savvy in — as you put it — “structuring the narrative” to achieve unified action around short-term goals. It is also fascinating how this is being done in large-scale social/political movements and also in hyper-local environments. Looking forward to your future posts on the subject!

Great analysis. What is your recommendation? Obviously, you have identified a few weak points and attributes of the protests but what should people do to actually effect change? Find leaders and start negotiations? Set an agenda? Create a new party or organize the opposition? Convince the media to get their heads out of their asses? Activate the army? Storm the prisons? Arm themselves? What is the right response to your government if they keep limiting your rights? Do you just leave the country? It’s a great analysis, but I feel that it lacks empathy for those involved.

Pingback: “questo problema di nome Twitter” | Alaska

Pingback: Analyzing the Turkish Protests | Mideast Matrix

Pingback: [BLOG] Some Tuesday links | A Bit More Detail

Pingback: A Remarkable Protest in Turkey ← Joshua Foust

Zeynep, as always, your insight is made powerful because it is rooted in evidence. The distinct media comparisons in your examples reinforce the orthoganalities you draw for Turkey versus Arab Spring and Occupy.

Pingback: The lesson #occupygezi gave to social media analysts | marcoRecorder

Pingback: Turkish Activists Crowdfund Money for New York Times Ad | Crowdfunding News

Zeynep, very good. Very, very good.

Pingback: The lesson learnt from #occupygezi: centralise your social media coordination | marcoRecorder

Pingback: To see the value of social media, watch what happened in Turkey when the regular media failed — paidContent

Pingback: Taksim halkindir- ¡Taksim es del pueblo! | Perifèries Urbanes

Pingback: Taksim halkindir- Taksim belongs to the people! | Perifèries Urbanes