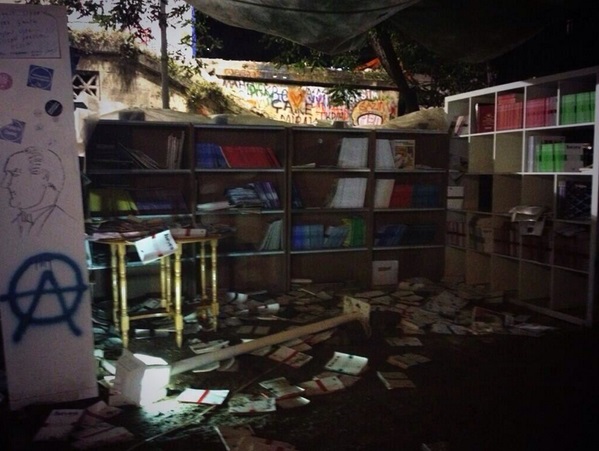

After the Gezi Park occupation was dispersed, dozens of neighborhood forums popped up around Istanbul where people get together to discuss a variety of issues. I’ve been attending these neighborhood forums, which are are organized in an “agora” format where speakers line up and take turns to speak. While media attention remains on the frequent Taksim Square demonstrations, the forums are lively, continue to be well-attended and are breaking precedent in Turkish politics which started with Gezi. To give a sense of the space, here’s the Abbasaga forum in Besiktas (at 12:30a on a Friday).

In Gezi, one thing that struck me and that I’ve been tweeting about, and that came up in many of the 100+ interviews I conducted with the participants was the spirit of tolerance and diversity. Gezi protests participation included people ranging from nationalist/traditional Kemalists to Kurdish political parties, from the “internet generation” youth (as they are referred to here) to feminists, from “revolutionary muslims” to many ordinary citizens who do not fit into any of these categories.

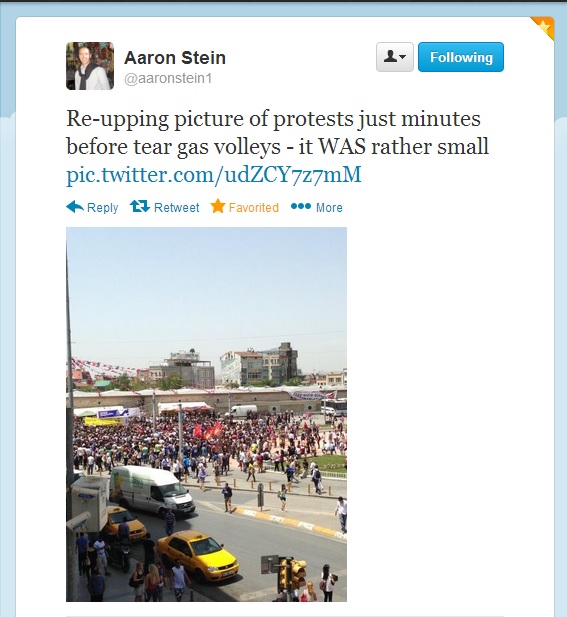

(By the way, the media, both here and abroad are missing the story–during the Gezi occupation, they concentrated on the occasional clashes in Taksim square. Now, during the neighborhood forum process, they still only cover Taksim protests. While important, that is not where the heart of the story is).

Many people I interviewed in Gezi told me that, for the first time, they found themselves talking with people with whom they had rarely interacted, with whom they had harbored prejudices, and with whom they had never had this kind of deep, political and substantive conversations. It emerged as the most personally satisfying aspect of the Gezi Park experience for many participants.

This unity was helped along by the police repression as well as Erdogan’s totalizing, polarizing rhetoric in which protesters were alternatively referred to as marginals, looters (“çapulcu” which became the term they adopted for themselves), terrorists, etc. Being stereotyped in so many negative ways helped create this identity of one of unity and tolerance within difference.

A famous photo from the Gezi Park period illustrates has become a symbol of this Post-Gezi politics in Turkey.

Running from the police in this picture are two youths, holding hands, one carrying a flag from the Kurdish BDP party and another an Ataturk (Kemalist) flag (ideologies that almost never speak to each other, or at least kindly). At the corner, another man makes the “wolf” sign that is traditional to ultra-nationalist Turks.

To be honest, had I not seen, interviewed in, and experienced Gezi myself, I’d be trying hard to figure out if this was photoshop. One can’t help by feel incredulous by such scenes in Turkey.

It is, however, a true picture–a pluralist generation has sprung up in Turkey under AKP’s strong rule partly because of it, and partly as a reaction to it. And that, mostly, is at the heart of the political crises that is fueling Gezi. This pluralism has no political expression and no real reflection in mainstream media, which is a little more than a government parrot these days, or even “opposition” traditional media which remains relatively firmly encamped in totalizing or outdated ideologies.

(A “dissident” TV station I watched last night –“Halk TV”– was trying to sell a “support package” which included pictures of Ataturk, stickers of Ataturk, flags of Ataturk, a book of Ataturk, a t-shirt with Ataturk’s saying and a poster of Ataturk–hardly an advanced political message in 2013 for a complex, diverse, modern county like Turkey. Such dissent, little more than repeated waving of many pictures of Ataturk, is not attractive especially to the youth, including secular youth, I spoke with in Gezi Park.)

In sum, in Turkey, there is no political party or institutional infrastructure which reflects this generation or this emerging pluralism. In fact, people often call this “Gezi ruhu” or “spirit of Gezi” to try to find a name for this unprecedented political coalescence.

I have come to think of this moment as an anti-postmodern pluralism. Unlike early stage (or, well, “traditional”) postmodern approaches, the “other” is not configured as an opaque, unknowable, “outside” entity. There is multitude but there is also unity and a unifying grand narrative–a unity that is based on empathy rather than a single model of the desirable. The “other” is knowable through common human experience and suffering. Hence, this is not like post-modernity which rejects unity or gran-narratives. In fact, it is striking how strong the grand, unifying narrative is among many participants.

In this non-post-modern pluralistic sensibility, there is an emphasis on shared stories but these stories are constructed not through erasing difference but through emphasizing empathy, tolerance and shared respect. Unlike traditional modernity which attempts to create one type of individual (a political ideology that characterizes both pre-AKP Turkey and, increasingly, post-AKP Turkey even though the “one type” being attempted has shifted significantly), difference is not fetishized, it is acknowledged as the basis of tolerance. “I’m against homophobia and islamophobia”, a young forum participant said, not seeing any contradictions in his stance: “I want the headscarf to be free and I want gay people to be free.”

As such, pluralism and tolerance are perhaps the most significant political values emerging in the post-Gezi politics.

For example, after a shooting in Kurdish Lice over tensions about building of new military posts, people in forums in Besiktas and Kadikoy, nationalist strong-holds, marched in support of Kurdish grievances. This would have been hard to imagine a month ago.

I have seen feminists conduct workshops in Gezi –specifically targeted to to soccer fans– on why they should not use misogynistic insults.

Muslim groups in Gezi distributed “kandil simit” –traditional for Prophet’s birthday– in Gezi and held prayers on that Islamic holy day.

I’ve seen Muslim groups praying in Gezi while a woman with crewcut, punk haircut –clearly not part of “them”– shood away journalists trying to take pics, who she thought was not respectful to their prayer. “They are praying, not putting on a show for you” she exclaimed and made the journalists keep their distance.

Perhaps the most interesting configuration to have emerged from the Gezi protests has been the LGBT community in Turkey. Long oppressed, it is also a community that has long struggled openly. Unlike other countries in Middle East, Turkey has a strong and burgeoning LGBT community that is increasingly coming out of the closet and organizing. Like other countries in the Middle East, they face grave prejudice and oppression.

LGBT neighborhoods (Turkey’s “Castro”) in Istanbul are concentrated around Taksim and Gezi Park is, so to speak, in their backyard. They were among the first protesters to try to protect the park and they have been central to its defense and organizing from the beginning. Along the way, they have acquired respect and status among many people who participated in the Gezi process.

Another key player in the Gezi protests has been “Carsi” –Turkey’s ultras who are fans of Besiktas soccer team. Carsi is known for their rowdy marches, bravery, somewhat unusual ingenuity which at one point involved hotwiring a back-hoe to push back against police APCs, and, unsurprisingly, their machismo.

Hence, some examples from the interaction between Carsi and LGBT organizations, two big players in Gezi Park resistance, illustrates the fascinating interaction emerging in this process. A favorite slogan for soccer fans in Turkey is “ibne hakem” or “the referee is a fag.”

Predictably, soccer fans adopted this slogan to politics in Gezi and started referring to various AKP officials as such. Predictably, the LGBT folk were not happy. They approach the soccer fans, Carsi, and asked them not to refer to AKP politicians –or others– as “ibne.” “We are the fags and real fags are here defending Gezi Park” they explained to the bewildered Carsi supporters who probably had rarely seen anyone proclaim the identity as a source of pride. However, Carsi had also seen the LGBT folk brave police repression–which the LGBT people explained is part of everyday life for them. Soccer fans, too, had often experienced clashes with the police. An understanding was not impossible.

After some back and forth, Carsi soccer fans countered that they might drop “fag” but they needed good insults. “How about sexist Erdogan?” was a suggestion from the LGBT contingent. So, this all ended with Turkey’s ultra-macho soccer fans chanting “Sexist Erdogan.”

In another instance in Gezi Park, I witnessed a Kurdish “teyze” (an older, traditional woman) from southeast Turkey in a heated, compassionate conversation with one of Istanbul’s better known transgendered activists. The dialogue, which I witnessed, was mostly about the need to love and understand each other’s suffering. During this conversation, the Kurdish “teyze” spoke in a thick, Zaza (a dialect of Kurdish) accent while the transgendered activist hugged the rainbow flag he had been waving and used speech locutions that are very specific to the gay community in Turkey. It ended up with them hugging in tears, vowing to keep in touch.

It also ended with me having to sit down to catch my breath that I had just witnessed what I had just witnessed.

I’m not sure I’d have believed all this was possible a month ago. Clearly, though, it was in the making–it did not come out of nowhere. Rather, AKP’s strong hand in governing has created constituencies for whom plurality and tolerance is a key value. As one Gezi participant said to me: “my problem is that this man [Erdogan] wants to paint us all black. We are a rainbow! There are many colors!” Hence, this tolerance was not just a momentary convenience, but a value that has emerged from an experience of feeling and being shut out.

It’s unclear how much this pluralism will carry on in the future–or how widespread it is in the country in general–but it is a striking and a potentially deeply transformative experience for the participants in the Gezi process as well as the ongoing neighborhood forums.

So, I come to today. In a few hours, the 11th LGBT pride march will start in Taksim. It is the first march with a “permit” in Taksim since the beginning of Gezi protests (though nobody really seems to be taking permits that seriously these days). Many groups, well, pretty much everyone, who has been a part of the Gezi protests will be attending. Most neighborhood forums I attended have expressed a desire to march as well.

This might be the first time that Turkey’s LGBT community leads –and is not just tolerated– a large and diverse march of dissenters whose unifying ideology is emerging as tolerance and plurality.

Today, in Turkish twitter, “#direnayol” is trending which brings together Gezi politics with LGBT symbolism.

In Turkish, “diren” means to resist and has become the symbolic word of the Gezi protests–“#direnankara” to refer to protests in Ankara, for example. When AKP youth floated a badly photoshopped image suggesting that the famous pepper-sprayed “women in red” was was an actress and the whole thing was a set up (there is ample video and multiple Reuters photos of the pepper-spraying incident), twitter users started joking with #direnphotoshop–resist, photoshop.”

“Ayol” on the other hand, is the Turkish linguistic equivalent of a “limped wrist.” It literally connotes a sense like “darling.” So, to say “gel, ayol” is a bit like saying “come, darling.” In Turkish “ayol” is also a symbol of gay speech, a locution that can be added to sentences to convey a queer sensibility. For example, “Ayol, it’s an actual revolution” (“ayol, resmen devrim”) had become a slogan of the LGBT community during the Gezi events.

During the Gezi Park Protest, a whirling dervish in a gas mask visited Gezi park (of course, right?) and the image was widely circulated, often along with the saying “Sen de Gel” — a saying meaning, “you, too, come”, from a sufi poem by Rumi.

Today, along with the #direnayol hashtag, the following image has been circulating in Turkish Twitter, uniting the LGBT rainbow flag (a very recognizable symbol in Turkey), the dervish, the gas mask, and the call: “You, too, Come.”:

The Rumi poem “Sen de Gel” is inscribed in his shrine in Konya, Turkey and was perhaps best translated in spirit by Coleman Barks:

Come, come, whoever you are,

Wanderer, worshiper, lover of leaving.

It doesn’t matter.

Ours is not a caravan of despair.

Come, even if you have broken your vows

a thousand times.

Come, yet again, come, come.

So, perhaps, I’ll end by answering a question many friends of mine have asking me–should I come to Turkey during these turbulent times? I’ll repeat the answer I’ve been giving all along. Yes. I’ve even joked that the unsafest part of my visit to Turkey was the ride from the airport in a taxi that had removed the seatbelt–and I mean it. Istanbul is a big city and usual big city precautions apply–and Taksim at the height of a protest is not advisable if you have children with you.

Other than that, yes, do come to Istanbul. Especially now. This is not a caravan of despair.