The latest sad news coming out of Turkey was the death of Berkin Elvan, a young boy, who just turned 15, who had been on his way to buy bread for his family in his own neighborhood, where people had also taken to the streets, during the Gezi protests. On the way, he was hit in the head by a tear gas canister and spent 269 agonizing days in a deep coma. Towards the end, his weight was down to 16 kgs from 45 kgs.

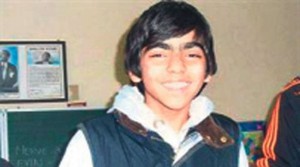

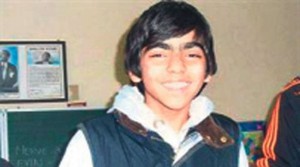

Berkin was the youngest victim as can be seen from his child’s face smiling from a photo taken among his friends at school:

Recently, his health had been failing and people were braced for bad news for the last few days. This morning, after his family tweeted out that “we had lost our son” news of the loss quickly spread in waves of grief that merged with waves of anger, heightened by the fact that nobody had been convicted for his death by a tear gas canister.

This makes Berkin the eighth death associated with Gezi protests, almost all of them young men, including a 19 year old who was beaten to death, and a 22 year old police officer who fell from a bridge during the events and whom the protesters always counted among those they mourn in their memorials. Pictures of his heartbroken family further entrenched the reality: he was just 15, he was on his way to buy bread and nobody was convicted for killing him.

The image of his grief-stricken parents clouded timelines with its raw grief.

Fury and sadness erupted online and offline. People took to the streets around Turkey. The hashtag, #BerkinElvanÖlümsüzdür (Berkin Elvan is immortal) trended worldwide, while another hashtag #HoşçakalBerkinim, “Goodbye my Berkin” also trended worldwide, in sad opposition to the wishes expressed in the first.  However, unlike what it may look like from outside, Berkin’s death did not renew protests out of the blue. Despite the latest focus on the corruption scandal and crisis within the judiciary, the “Gezi protests” had never disappeared. Instead, lacking a focus or political outlet, the discontent simmered both through occasional protests (over the Internet censorship law, for example) and also online.

However, unlike what it may look like from outside, Berkin’s death did not renew protests out of the blue. Despite the latest focus on the corruption scandal and crisis within the judiciary, the “Gezi protests” had never disappeared. Instead, lacking a focus or political outlet, the discontent simmered both through occasional protests (over the Internet censorship law, for example) and also online.

The lack of political outlet for the Gezi dissent is a circular question: it was lack of political outlet (due to ossified political system and concentration of power and media censorship) that caused the Gezi eruption in the first place. The Prime minister of Turkey often said that the Gezi protests were not just about the trees, that they were subverted for other causes. Based on the interviews I did at the park, I can vehemently deny one charge that is often made: that a desire for a military coup was among the demands of the protests–such an option almost never came up, and was not mentioned as desirable by the hundreds of protesters I interviewed. On the other hand, it is true the protests were more than about a park and hence have not dissipated because the park was spared. The protesters I interviewed at Gezi talked about a desire for rule of law, their concerns about growing corruption (which would erupt in a scandal about six month later), their fears that concentration of powers had gone too far and that spaces of freedom and of choice were being constricted by a government that wanted to dictate everything. Those concerns have not gone away; if anything, the last nine months deepened the fault lines.

For 269 days while Berkin fought to hang on to life, people remembered him daily on social media. Hashtags would pop up: #uyançoçuk or “wake up child”, and someone would tweet out his name in sadness mixed with hope. His family acquired a widely followed Twitter account and regularly updated people. His innocent frame, his thick eyebrows and smiling eyes became a symbol of hope against the violence that threatened to steal his young life and his future. A few days ago, news started coming out that his heart had stopped, twice, and he was clearly deteriorating. As usual, all these conversations mainly occurred on social media as mainstream media, mostly silent during Gezi, still barely discussed these topics.

Another aspect of Berkin’s death that is deeply evocative in the context of Turkey is that he was on his way to buy bread. Bread is quasi-sacred in Turkey. In Turkey, it is the source of nourishment and it represents both human labor and God’s bounty through nature. If a piece of bread falls to the ground, my grandmother kisses it after picking it up from where it fell. Wasting bread is seen as a sin, and not having bread at a table will get you howls of protest from people who will tell you they’ll be hungry without bread. (Yes, in Turkey, people will eat bread with pasta, for example).

In short order, “Berkin and bread protests” popped up around the country. As with previous waves of novel tactics, it started with one person who did something that others quickly picked up–almost all through social media. In this case, people in public places sat in front of a loaf of bread, in silence, sometimes with a picture of Berkin’s young, fragile face now symbol of loss and devastation. It started with one person:

Then she sat down by him:

Then she sat down by him:  Soon it was crowd:

Soon it was crowd:  And then the pictures spread on social media, and occasionally picked up by online newspapers. And people elsewhere started doing it:

And then the pictures spread on social media, and occasionally picked up by online newspapers. And people elsewhere started doing it:

A house in Berkin’s neighborhood placed a loaf of bread in a grief-stricken ribbon outside their door:

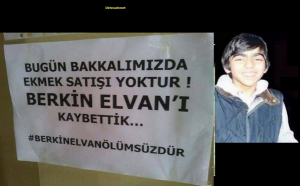

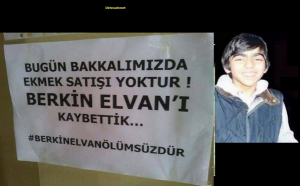

A house in Berkin’s neighborhood placed a loaf of bread in a grief-stricken ribbon outside their door:  Some shops declared that they would not sell bread that day, and even put hashtags in their signs which perhaps best exemplifies the way in which online and offline have meshed in one inseparable reality in fueling these waves of protests:

Some shops declared that they would not sell bread that day, and even put hashtags in their signs which perhaps best exemplifies the way in which online and offline have meshed in one inseparable reality in fueling these waves of protests:  As I type this, there are protests in multiple cities, including in Istanbul and Ankara, which are reportedly being dispersed with heavy use of tear gas and water cannons–the same cycle that triggered waves of discontent since Gezi protests erupted less than a year ago. My timeline is full of familiar images of protesters, police and streets under cloud of gas.

As I type this, there are protests in multiple cities, including in Istanbul and Ankara, which are reportedly being dispersed with heavy use of tear gas and water cannons–the same cycle that triggered waves of discontent since Gezi protests erupted less than a year ago. My timeline is full of familiar images of protesters, police and streets under cloud of gas.

However, whenever there is something new, it quickly breaks on social media. For example, in Ankara, police reportedly used a new kind of canister which was quickly shared on social media as people searched for answers. (In Gezi, people had become tear gas canister experts. People collected them and carefully discussed their differential effects the way foodies discuss coffee or olive oil). Students in ODTU, Ankara, made fun of these new capsules which they had never seen before, while asking for help identifying them:

As the spiral of protests spread around Turkey, Berkan Elvin’s family called for a mass protest/funeral for their son for tomorrow, the 12th of March, at 2p. They called for this funeral via Twitter, of course, the key conduit for information dissemination for protesters as well as for supporters of the government who are also online in large numbers.

They used a “screen capture” a widespread method on Twitter used to circumvent character limits and also for algorithmic invisibility. In Turkey, people will sometimes reply to each other via “screenshots” of the other person’s tweets rather than linking to them or mentioning them. This is done as a means to deny attention, to remain invisible to automated systems (as one will not show up in other person’s connect tab) and also to effectively “talk behind someone’s back.” In fact, what may look like great polarization in the Twittersphere in Turkey effectively hides the multiple methods by which opposing parties will engage each other directly, sometimes even carrying out conversations back and forth, in a manner that would be invisible to anything but qualitative analysis (you gotta read and understand, in other words, not just scrape big data). Screenshots, subtweets, and following by going to individual web pages rather than formally following are methods galore in Turkish Twitter, at least in its political parts which, these days, seem to expand very quickly.

This is a sad day in so many dimensions. It is a sad day for Turkey: a country with so much potential, mired in a crisis of political representation, legitimacy, concentration of power and collapse of rule of law.

Today is also a sad reminder that so-called “non-lethal” weapons like tear gas canisters are, indeed, often lethal. The first responses to my tweets about Berkin’s death came from Bahrain, a country that suffers from cycles of protest and repression where tear gas is used to break up peaceful citizen assemblies.

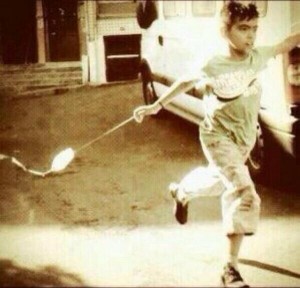

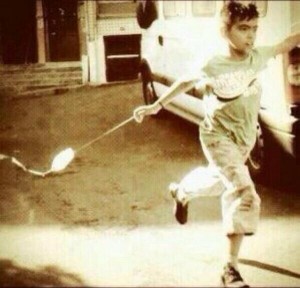

Most of all, though it is the saddest day for Berkin’s family and loved ones. Perhaps the most piercing picture to circulate today was from Berkin’s childhood, which he never had a chance to grow out of. Spotting a mop of hair and his unruly eyebrows, Berkin is seen trying to float a make-shift kite in the streets, as children from poor families can be seen all over Turkey. His kite is small, he has narrow streets rather than open parks to run in, and the kite struggles behind him as he runs, determined to make it fly with all the seriousness the quest deserves: everything.

Did he ever manage to make his kite fly? We’ll never be able to ask him as the world run by grown-ups who will never understand how such a thing could be so important, struck him down before he had a chance.