Journalists won’t admit this often, but they tend to be pack animals. I got my first sense of this while hanging out with foreign correspondents and journalists in Turkey–and I later worked with international news organizations as a local organizer and translator. All the journalists, and all their camerapersons, and all their crew, and even their local workers seemed to not only know each other very well, they were almost always together. You could literally spot them from a distance as a large mass of people with their gear, lights and correspondents fixing their hair before going on the air.

Staying in the same hotel. Hanging out in the same bar. Attending the same press conference. Going to the same event. Taking the same picture from near-identical angle.

Packs often made their decisions collectively as well. While I was in Diyarbakir, Turkey, for example, with one of those large packs covering ongoing unrest Northern Iraq, we were told that the roads were unsafe and travel was not possible via the usual routes. The journalists pushed and prodded and looked for alternative ways—but, in the end, “the pack” gave up and settled into an uneasy wait, eating kebabs and watermelon in the lovely “Kervansaray” hotel we were all staying in. (Yes, journalists also all stay in the same hotel because there is often only one reasonable hotel in an area).

Some, though, abandoned the pack. Christian Amanpour, for example, took off in the middle of the night through a circuitous mountain route. And I know she made it because I ran into her about a week later at the border when she approached me out of the blue and said, “Hey, are you Zeynep?” Yes, I said, and I ventured a guess that I just woke up in an alternate universe where I was the notorious one instead of her. Truth was, a producer I was working with had asked her to look for me to deliver a message–and there weren’t that many petite brunette women hanging out at the border in what was then a serious conflict region. My alternate universe was deflated but she was indeed in an alternate universe than my pack as she had been in Northern Iraq the past few days while we waited.

This awareness that traditional journalism is often poorly-sourced, and what appears as many reports is actually a single report, is partly why I was encouraged by the explosion of citizen journalism enabled through social media. News outside the pack, I thought. Many, many, many sources of news instead of the eyes of a united pack.

I understand why journalists stay in those packs—they are often navigating their own way around unchartered territory, worried about safety, and also worried about being scooped. If everyone has the same story, more or less, things are okay, more or less, professionally.

But it certainly results in poorer, thinner news. With shrinking number of foreign correspondents, and with too few correspondents covering too many countries (too big a beat – how can one person cover all of Middle East?), and too little time in any one country, it just makes sense to stick together.

However, journalism isn’t just about multiple sourcing. Journalism also isn’t only about knowing the area one is covering, but it is also about knowing the audience one is communicating with, knowing how to evaluate and bring facts together, and knowing how to evaluate and tell a story to that particular audience. It’s a two-way street with competencies required on both sides of the equation, both compiling and presenting the news.

Hence, we still need journalists who can stand between the multitudes of citizen journalists and news sources to apply the craft of journalism to produce the best stories: to construct narratives, to evaluate news and rumors, and finds ways to most effectively communicate with the audiences.

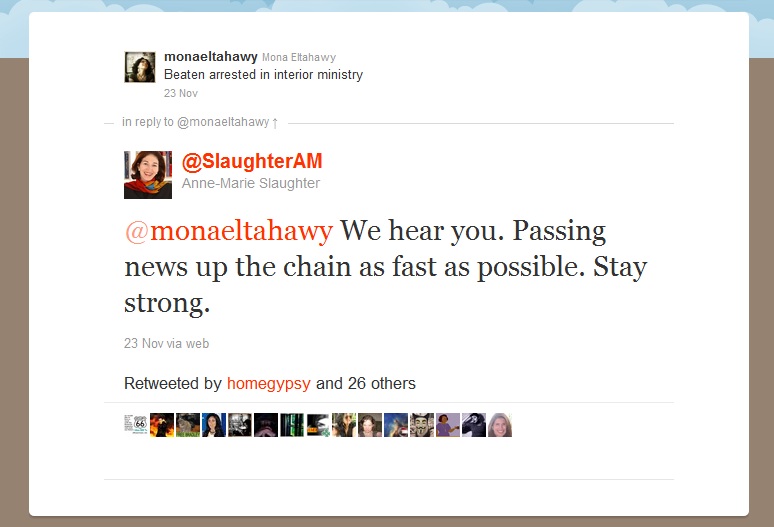

One such journalist to emerge in the last year’s events has been NPR’s Andy Carvin who’s been “anchoring” a Middle East based newsfeed on Twitter since December of last year when the Tunisian uprising began. His timeline has emerged as an “oral history”, a curated story, and an important source of on-the-ground news from the uprisings sweeping the region. Another example is Robert Mackey who writes “The Lede” blog for the New York Times and often covers very important stories.

However, there has also been backlash and rejection of this kind of journalism. The criticisms are not invalid and should not just be dismissed as old-fashioned. While many accept that it is useful, a common issue which comes up is: “how do you know what you hear on social media is true?” I think that is an important question and one that requires a lot of thought and study and expansion of the craft of journalism.

Here, I want to examine some aspects of that question to highlight a key difference between traditional journalism (and its shortcomings) and social-media-based journalism (and its shortcomings).

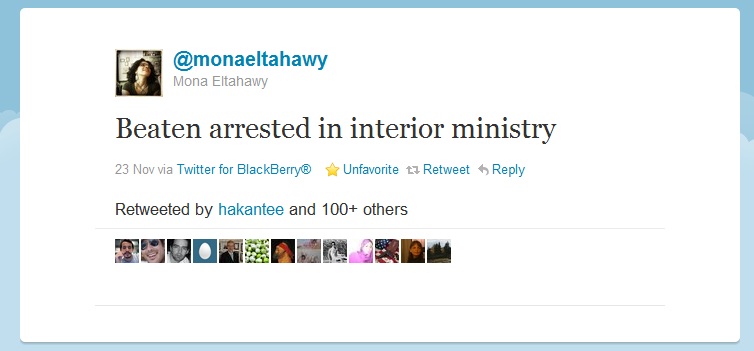

My case study begins yesterday when the prominent Egyptian newspaper Shorouk posted an article stating that prominent Egyptian blogger Alaa Abd-el Fattah, whose case was recently transferred from military to civilian courts as a result of pressure from Tahrir and elsewhere, was now charged with premeditated murder, among other charges, for his activities the night of the Maspero killings in Egypt which resulted in the death of 27 Copts during a protest march. Alaa is well-known by many people in the West (including Andy Carvin and myself) and the charges were fairly ridiculous even before premeditated murder were added. Alaa is a lifelong activist and blogger and he had written extensively about his efforts that night in question and it seems pretty clear that his effort was all about documenting the killings–and the idea that he’d be out there with guns killing people was quiet shocking, pretty impossible to believe, and also a potential capital offense—putting the life of one of Egypt’s best thinkers and democracy activists on the line.

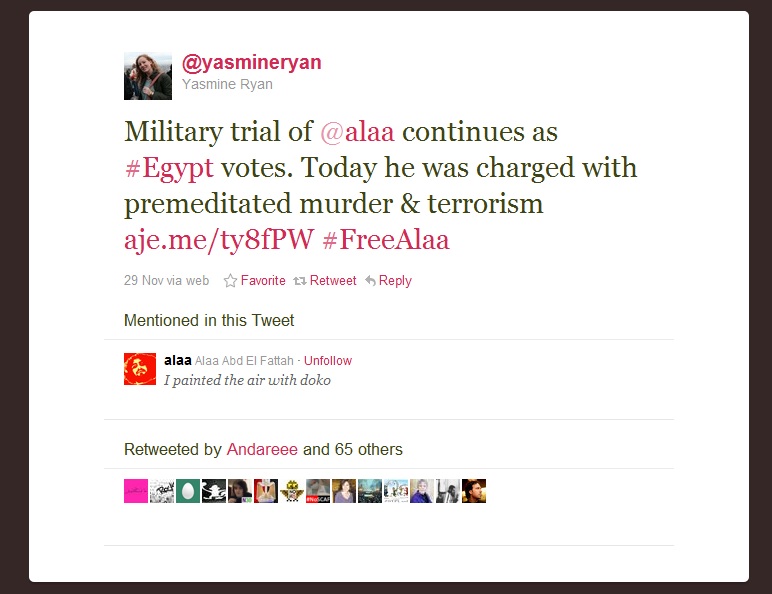

It starts with this:

Just as Andy Carvin started asking around for confirmation on this story, Al Jazeera English posted an item reporting the same story on its story. However, that too, was based on reaction to the Shorouk piece and did not have independent confirmation.

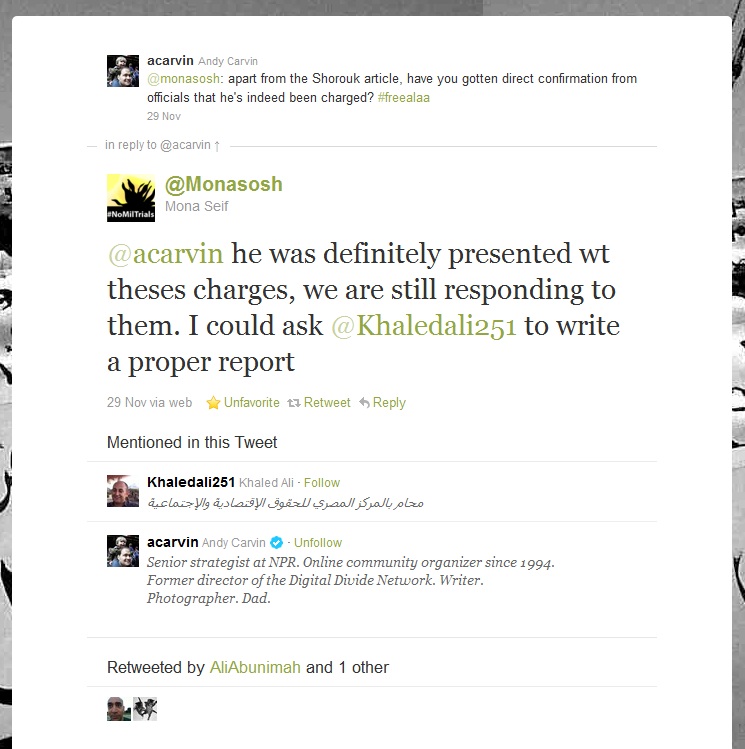

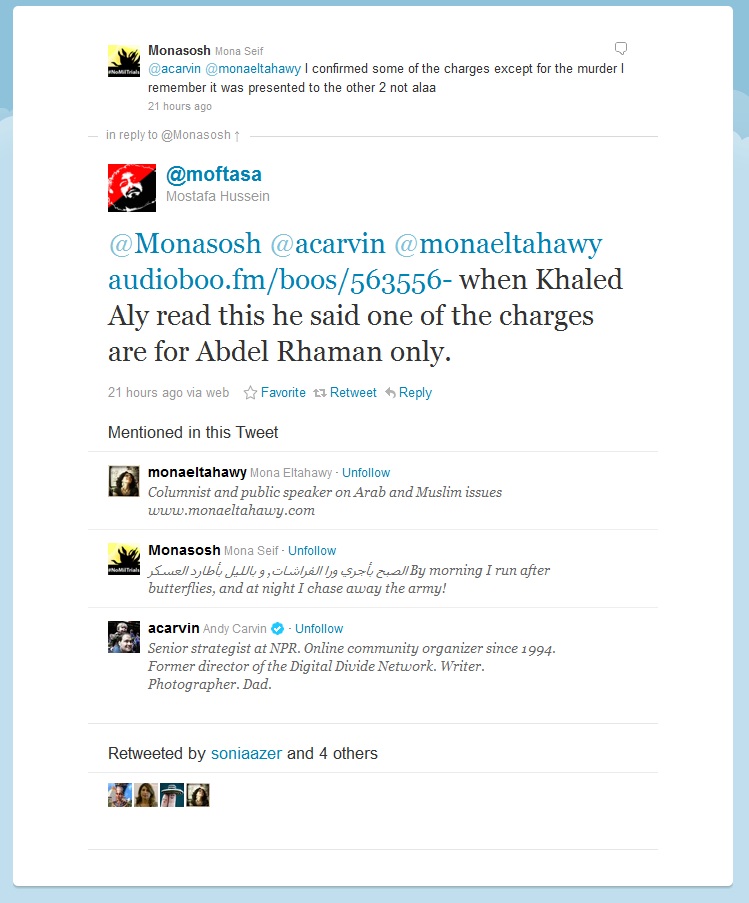

I was not yet paying attention to this story at the moment but soon after, a key development, as far as I can tell, occurred, through Mona Seif, Alaa’s sister who also leads a campaign against military trials and is thus quite knowledgeable about the court system:

Soon after I saw Andy Carvin’s reporting *and* his exchange with Alaa’s sister, the Shorouk article was translated verbatim. The statement was very clear and it appeared that the charges now included premeditated murder. Alarmed by the statements from Alaa’s sister, I sent out tweets stating this news. While there was heated discussion of this issue, more Egyptian news organizations jumped on this topic, reporting the same news:

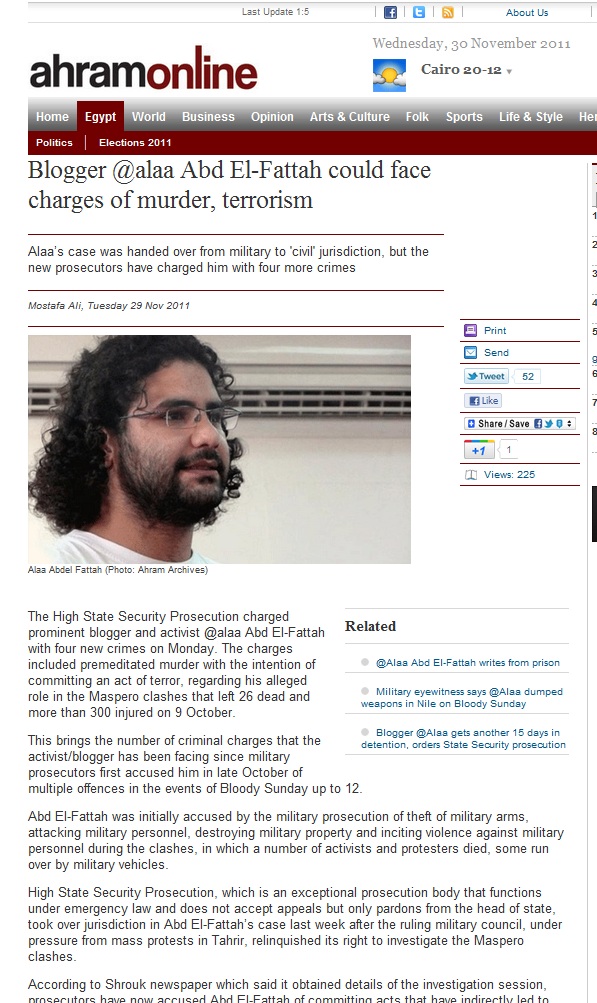

Ahram Online:

Bikya Masr:

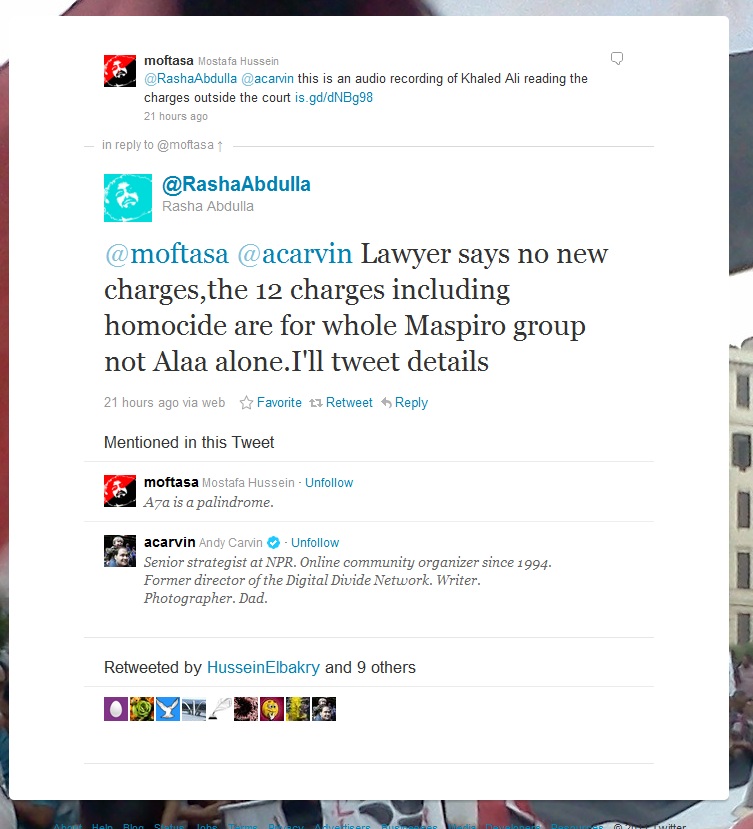

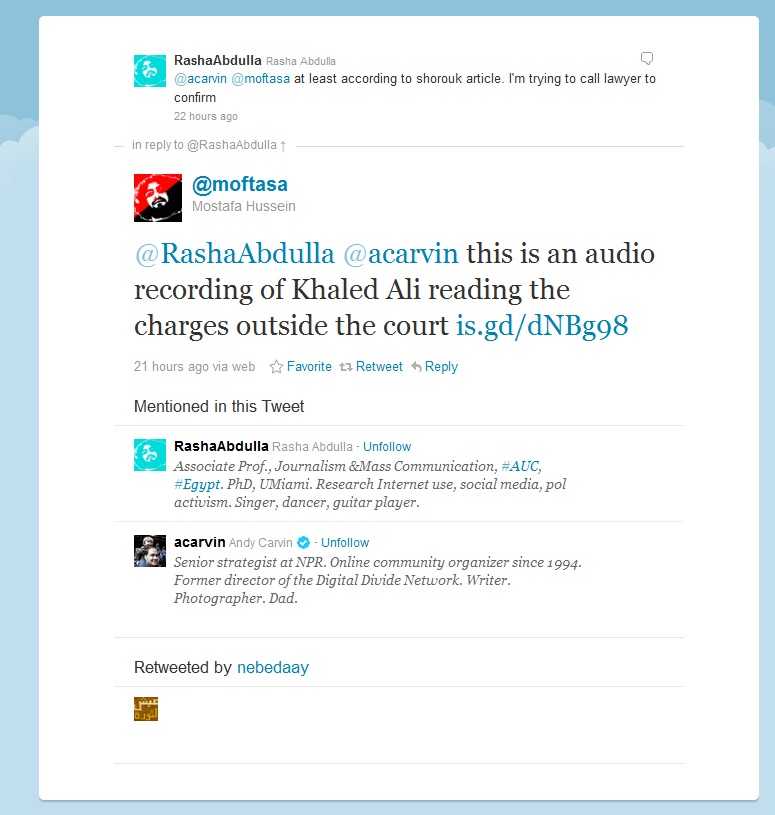

However, it soon started emerging that maybe Al Shorouk had it wrong. Another twitter user and physician Mostafa Hussein posted the audio of Alaa’s lawyer explaining the charges, and twitter user and AUC professor Rasha Abdulla reached the lawyer by the phone.

As a result of the efforts of these two citizen journalists, it soon became clear that the charges likely included no new charges and that Shorouk likely got the story wrong:

(Although later that night, Alaa’s sister posted this answer to me which seemed to suggest there might be “group charges” including Alaa, although Alaa’s wife @manal, seemed to think not). In the end, though, it seems that the correct story is that there are no new charges, and the process is just convoluted and confusing for many.

The full story of how it played out can be seen in this Storify by Andy Carvin.

LESSONS AND TOOLS

This case is very informative in identifying weaknesses and strengths of social-media based journalism. Let’s look at how it works best and how it fails, as it did in this case.

1- Triangulation needs to be more explicit and cautious. The strength of social-media based journalism lies in its ability to deviate from the “pack” behavior, which as I explained often necessarily dominates traditional news reporting. (To be clear, I am not just blaming traditional journalists; this is a structural issue. Too few journalists are covering too varied stories and this forces them to stick together to well-beaten paths).

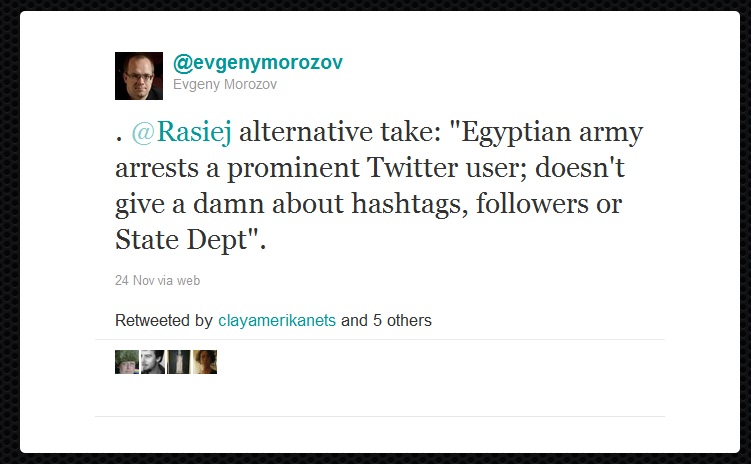

However, as we saw in this story, online cascades can also be a kind of pack behavior as well. Al Shorouk got echoed by Al Jazeera which got echoed by Andy Carvin, which got echoed by even more news outlets, which got echoed by many of us. Hence, when triangulating, it is important to make sure that it is not an echo chamber but genuine multiple reporting – and that can really be best done by incorporating more citizen journalism as well as more professional journalists into the mix.

2- Evaluating personal confirmation at cross-cultural, cross-linguistic transition point remains the weakest inflection point. In this case, I was aware that Al Jazeera’s reporting was not independent; however, Alaa’s sister seeming to confirm the case was a clincher for me. It turns out to have been a possible misunderstanding.

Thus, when communicating with people in different cultural/linguistic settings over social media, there needs to be better ways of evaluating the information and also being more explicit about needing more sources. Traditional journalism doesn’t always do that well in this regard either, but the process is more opaque and less visible (good journalists, however, are the ones who do this well). The visibility of the process in social media-based journalism makes it more open to criticism about errors, which are also more visible. This transparency should be seen as a moment for improvement, not for returning back to the days of more opaque, unclear paths.

This is a potential moment to address one of the biggest weaknesses in foreign-news journalism, that journalists are not part of the story they are writing and are, almost by definition, lacking in understanding of the context, by combining it with traditional journalism’s greatest strength over citizen journalism, that journalists are not part of the story they are writing, and thus are in a position to better evaluate multiple points of view and news with careful verification and a skeptical eye.

Whether citizen or professional-journalism based, the greatest threat to developing a factual, contextual narrative across borders and cultures occurs at that inflection point when news, information and viewpoints are being transferred from one country/person to another country/person, especially through a language barrier. (Yes, I’d love to see more Arabic speaking American journalists who specialize in covering Egypt, for example.) Social-media based journalism makes that point much more visible and scrutinizable. Such scrutiny should be welcome and stronger methods developed.

3- Traditional journalism is one more source (often a good, but not perfect one): Too often, many of us treat traditional journalism as infallible even though we know better. For example, many people got taken in by fake blogger “Amina” because the Guardian published an interview with “her” with a Damascus byline – without failing to mention that it was not an interview in person; rather it was conducted over email. Traditional news organizations should be treated as important but not infallible sources of news, especially when reporting about social-media based reports as some their reporters may be lacking key skills in operating in this new medium. (It is not a coincidence that Amina was unmasked firstby Ali Abunimah and Andy Carvin and Liz Henry, all of whom are experienced in evaluating social media information, and not traditional news organizations.)

4- Process Journalism vs. Product Journalism. The key difference between a traditional news organizations and social-media reinforced journalism is often in the visibility of the process versus the presentation of a final product.

One reason that social-media journalism comes under fire more often is that the process is more transparent, and necessarily includes more explicit errors, which are almost always corrected rather quickly, but through a messier process. While traditional journalism, too, admits their errors, the news is presented as a product, not a process. Hence, when New York Times made egregious errors in the reporting of the alleged weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, errors it was challenged on *at the time* as it was making them by many experts and other news organizations but which the Times ignored, the consequences can be devastating as many other news organizations take the lead of New York Times and also because many people trust it.

While these errors were corrected many years later, and the New York Times issues a lengthy apology, the war was done and hundreds of thousands of lives were lost or destroyed. Errors in social media, however, tend to get corrected much more visibly and quickly as the challenge itself is more visible and apparent. Hence, it’s just not the case that product journalism, which presents products in an infallible-seeming manner is always the best journalism. Integration of visibility into the process (less reporting about what “senior unnamed sources leaked” for example, as that is an obscuration and should be done very, very judiciously rather than as a routine process) and more explicit integration of factual challenges would improve all journalism.

However, process journalism has significant issues as well:

5- Process journalism is more demanding from the audience. Even long after correct information about Alaa’s charges came out, tweets replicating the earlier, incorrect information were reverberating through social media. There is a two-fold problem here, one which replicates problems with traditional journalism and one which goes beyond it.

First, in traditional journalism, too, corrections are seen by fewer people than those who see the original incorrect information. However, in social-media based journalism, since the process is more transparent, there are bound to be more error-corrections. At the moment social-media based journalism requires great effort and attention to follow.

For example, the number of people who retweet an original tweet are often far greater than the number who will retweet a correction. Considering that a tweet may then be re-re-retweeted through a network, it becomes hard, if not impossible, to ensure a correction reaches all those it should. (In the Turkish press code, which is hardly exemplary in other respects, court-ordered corrections have to be issued *in the same place with the same font* as the original story. That should be true for all corrections whether in traditional or social-media based journalism but how to achieve that remains elusive).

In other words, while many people may just want to eat the sausage, social-media requires that not only one watch sausage being made, one watch very carefully. That is not a reasonable expectation if a more democratic, wider and correct information diffusion is a goal as systems requiring more effort almost always increase inequalities. The rich –those with attention, time and know-how– will likely get richer while others will be left behind confused.

Yes, we need more people to understand better how the sausage is made, and sometimes watch how it is made, it is not reasonable or a positive contribution to the public sphere if only the people who have the time, attention and resources to watch and understand the whole process are able to enjoy its fruits.

Some suggestions:

So, should we give up on social-media based journalism because it is messier and more demanding? On the contrary, as I argued, it provides us with a important resource to address some of the shortcomings of traditional reporting. I propose three avenues to explore:

1- Journalists like Robert Mackey, Andy Carvin and others who straddle worlds of social-media generated citizen journalism and traditional journalism are key to ensuring that this emerging resource is made accessible. Often, Mackey’s “The Lede” blog and Carvin’s feed become key sources of important news which is otherwise not covered much, if at all, by the traditional sections of the organization. It’s not that we need social-media journalists, but beat journalists who know how to incorporate social-media as a key resource.

Journalism schools need to classes which teach these skills, and news organizations have train people on them. Some of these skills echo those of traditional journalism, while others are novel ones. (How to detect sockpuppets (developing a “sockdar”), how to triungulate citizen reports, how to find conversations about a particular topic, etc., for example.)

2- We need better technical tools as well as more people using them. Tools such as “storify” which allow one to “make a story” out of tweets are useful but are barely the tip of the iceberg of what’s needed. For example, it would be great if one could “tag” tweets as “if you accept this tweet, you also accept one more tweet to be sent later.” This could be an opt-in feature and be limited to one tweet per original tweet. I certainly wish I was able to reach everyone who might have seen my earlier, later shown to be incorrect tweets.

Many tools are needed and someone needs to create them. I was happy to recently hear that Columbia school of journalism has five students majoring in journalism and computer science. May this model spread, and may developing new platforms for journalism also be seen properly as journalism–as it requires a proper understanding of the craft and process of journalism, not just how to code, to create these tools.

3- Pack behaviour of traditional journalism is sometimes being replicated in the cascade behaviour of social-media based journalism. This can be fought against by incorporating *more* citizen journalism and openly encouraging challenges. @Mostafa and @Rashaabdulla, in the end, were the ones that did the journalistic leg work in this story and neither are professionals but both are known as careful and trustworthy individuals. This brings us back to the importance of beat –I trusted Rasha’s reporting, for example, because she is a a fellow professor, social scientist and a colleague and I know her to be careful with facts. For me, it wasn’t about “oh, here’s a tweet” but more about “oh, here’s a person with a solid reputation.” This is no different than what traditional journalism does.

In the end, I’m arguing for neither pure process journalism, which is cumbersome for the audience and will likely increase inequalities in the public sphere, nor product journalism, which hides its errors and process under the rug, but a new merger which is aware of its strengths and weaknesses, with strong commitment to factual reporting, context, triangulation, evaluating of sources, claims and facts, as well as an explicit welcoming of challenges, and, above all, welcoming the visibility of errors not as a reason to abandon contributions from citizen journalism, but as an opportunity for improvement and enrichment.