As I follow the remarkable political transformations ongoing in the Middle East and North Africa through social media, I’m struck by the depth of the difference between news curation and anchoring on Twitter versus Television. In this post, I’d like to argue that Television functions as a distancing technology while social media works in the opposite direction: through transparency of the process of narrative construction, through immediacy of the intermediaries, through removal of censorship over images and stories (television never shows the truly horrific pictures of war), and through person-to-person interactivity, social media news curation creates a sense of visceral and intimate connectivity, in direct contrast to television, which is explicitly constructed to separate the viewer from the events.

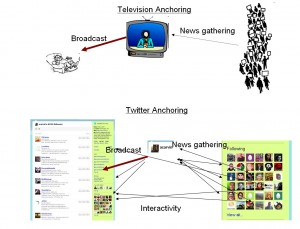

Although it is the first factor most people think of, I believe that the distancing effect of TV isn’t just because TV is broadcast and social media is interactive. In fact, while the potential for interactivity is a significant factor, most people interact with only a few people on social media and people who act like news hubs do mostly broadcast—their messages reach many. (Check out this brand new study). I think the substantive differences also lie elsewhere and in this post, I want to examine two key mechanisms which alter this sense of distance: the construction of the role of the anchor or the curator, and the role of content filtering.

On television, the traditional broadcast news anchor is explicitly distant and unmoved by the events he or she is covering. This distancing is structured through the visual framing (sitting upright, staring ahead, crisp but predictable intonation, professional and muted dress), the effortless but abrupt transition from story to story. (“Now I am going to tell you about starving children. Next up, a new treatment that can ease your wrinkles. Later: will it rain tomorrow?), the semi-frozen, plastic demeanor of the anchor no matter the story and the clear lack of personal involvement or concern, and the constant interruption by ads—a very surreal and disorienting experience unless one has been thoroughly conditioned into accepting them as normal. All this positions the anchor between us and the event and signals to the viewer that the event is merely something to be watched, and then you move on.

Compare that to the closest example of an anchor which has emerged during this period. I’m going to use Andy Carvin, who has been curating and anchoring about the uprisings since they began in Tunisia, sending hundreds of tweets and retweets per day usually from early morning into the night, as an example.

Carvin himself compares his role to that of an anchor, except with his Twitter followers as his producers and his news sources rather than traditional professionals. However, there are significant differences. First, Carvin is immersed in the story. He does not move from unrelated topic to unrelated topic the way a traditional news anchor does. Second, his tweets are his own words so we have a distinct sense of a person between us and the events rather than a figurehead reading words from a teleprompter he or she did not write or think. Third, he does not construct his position as one of distance and uncaring. He is not hiding his opinions or sympathies. Fourth, his news gathering and curation process is transparent–and that evokes a different level of engagement with the story even if you are only a viewer of the tweet stream and never respond or interact. I believe the fourth point is often underappreciated.

With Carvin’s constant and transparent efforts at verification and confirmation, the followers get a visceral sense of how news is “cooked.” Rather than the “final” package we encounter on television, delivered to us as a relatively infallible, ready-to-consume, product for us to uncritically accept, on Twitter curation feeds, we are often in a position to observe the process by which a narrative emerges, trickle by trickle. “Polished” and “final” presentation of news invites passivity and consumption whereas visibility of the news gathering process changes our interaction with it into a “lean-forward” experience. Carvin’s reporting is not infallible–although most of the stories from citizen-media sources often turn out to be fairly accurate, belying the idea that Twitter is a medium in which crazy rumors run amok—but it wears that fallibility on its sleeve and is openly submerged in a self-corrective process in which reports and points-of-view from multiple sources, including citizen and traditional media, are intertwined in an evolving narrative.

Thus, the process engages the “audience” not necessarily because most of Carvin’s tens of thousands of followers actually will contribute to the story or interact directly with him or his sources but because, unlike the opacity of modern production systems in which everything is delivered to the consumer shrink-wrapped, “cleansed” of hints of its origin and the process by which it was produced, news curation on Twitter is somewhat holistic, messy, and very much connected with its origins .Consequently, the foibles and pitfalls –the unverified stories, the difficulty of getting reliable news from closed regimes and war-zones, translation issues, misunderstandings—are viewable by the audience in real time.

This visibility of the process is a step in the opposite direction from French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s famous assertion that we are increasingly moving towards a “procession of simulacra” in which the simulation (“the news”) increasingly overtakes any notion of the real and breaks the link between representation and the object –often in the form of spectacle–, ultimately erasing the real. Baudrillard famously wrote a series of essays titled “The Gulf War Did Not Happen” – he was not claiming that bombs were not dropped and people killed. Rather, he had argued that, for the Western audiences, the First Gulf war was experienced merely as green flickers on TV screens narrated by familiar anchors and without much connection with actual reality – reality as inhabited by human beings at a human scale.

Censorship and Graphic Content : Shrink-Wrapped Humanity

One important way in which the curator/anchor role differs on Twitter compared to television relates to the second mechanism, the availability of unfiltered, graphic content. There has been a steady stream of photographs and videos depicting the reality of war and violence: images of the dead, dying and wounded of all ages, from small babies to elderly men and women have been circulating on social media sites. Understandably, victims of such violence did not feel a need to censor their very real suffering and keep it from us, the way television steps between us and the victims and isolates us, the audience, from reality.

After months of such coverage, I have found it harder and harder to look at more photographs and I do understand the need to provide mechanisms by which people can choose not to look at a particular photograph at a particular moment. Such images have been haunting my dreams and I’ve chosen, for the moment, to stop looking at any more. So, this is not a blind endorsement of flooding everyone with images of death and gore; I understand that there are awful things happening somewhere, every minute, and we cannot always be immersed in such misery and sorrow.

However, I am firmly of the opinion that the massive censorship of reality and images of this reality by mainstream news organizations from their inception has been incredibly damaging. It has severed this link of common humanity between people “audiences” in one part of the world and victims in another. This censorship has effectively relegated the status of other humans to that of livestock, whose deaths we also do not encounter except in an unrecognizable format in the supermarket. (And if anyone wants to argue that this is all done to protect children from inadvertent exposure, I’d reply that there are many mechanisms by which this could be done besides constant censorship for everyone.) While I cannot discuss the reasons behind this censorship in one blog post, suffice it to say it ranges from political control to keeping audiences receptive to advertisements.

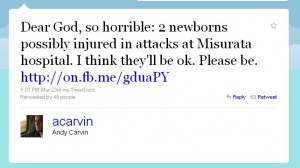

Such images take a visceral and deep toll, and the fact that anchors do not pretend to be unaffected increases their immediacy. After a particularly harrowing video showing newborn babies in a damaged hospital, Andy Carvin started tweeting about how shaken he was:

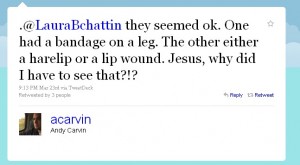

Soon, a pediatrician and a neonatal unit nurse stepped up to assure Carvin—and the rest of us—that the babies seemed okay and rather than being injured, one appeared to be born with a cleft palate. In most other cases, however, the news was not so good and pictures of dead or wounded children floated around Carvin’s stream.

I am not arguing that we would look at hurt children and be unmoved were it not for Carvin’s open display of emotion. I am arguing that traditional news anchors effectively invite us to do just that: to distance ourselves.Humans naturally react to suffering and it takes a very contrived environment to dampen that response. Other examples I mentioned as emerging anchor-hubs also display this tendency: they react to horrific news with appropriate horror.

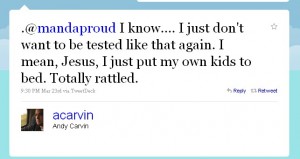

By not playing the traditional game of journalistic disconnectedness, the emerging Twitter anchors are inviting us to remain human, to react, to cry, to be outraged, to feel helpless, to be moved while the television anchor appears only to care that we do not change the channel during commercial break. Thus, watching Andy Carvin deal with his own vulnerability to imagining children hurt –children just like his– dramatically creates a mechanism in the opposite direction of that created by traditional news.

And our distance to events around the world is of crucial importance. In a fascinating book about the science of killing, (“On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society”), Dave Grossman traces the role distance plays in the psychological cost of harming another human being. Contrary to assumptions, virtually everyone who does not fall into the rare breed of aggressive psychopaths who kill with ease has to be trained to kill. To the chagrin of military trainers and leaders throughout history, humans have an innate aversion to taking of human life. Untrained soldiers are historically averse to killing the “enemy” even when their life is in direct danger. Most will hide, duck, fire in the air, load and unload their weapons repeatedly, fire over the heads of the “enemy” and take other evasive actions, anything, to avoid killing. For example, in World War II, only about 20 percent of the riflemen were found to actually fire their weapons directly at enemy soldiers.

As Grossman explains it, every new military technology that increases the distance between the soldier and the person who is being attacked increases the rate and ease with which soldiers will obey orders to kill. Thus, bayonets are psychologically hardest to use and much more difficult than rifles even though rifles kill more people more easily. Artillery is easier, especially manned by multi-person crews which create an environment of “mutual surveillance”, making it harder to take evasive action by the soldiers. Planes are the easiest of all. In fact, the rates of PTSD among soldiers follow this pattern quite directly; pilots, who often end up killing the most number of people, are less likely to suffer from PTSD compared to combat troops who deal with the “enemy” at a very close and personal level.

So, I propose that Twitter and social media curated-news distribution is quite different compared with traditional news dissemination through television. Twitter-curated news often puts us at bayonet distance to others –human, immediate and visceral– while television puts us on a jet flying 20,000 feet above the debris –impersonal, distant and unmoved.

There have long been concerns that “drone-wars” would create a playstation mentality among the soldiers, controlling robotic aircraft from thousands of miles away, isolated from the effects from their actions, going home at night, they would kill more easily and readily. (Ironically, it turns out drone operators do suffer from increased rates of PTSD because unlike pilots of jets or even artillery operators, they spend a lot of time viewing high-resolution pictures of their targets before and after bombing).

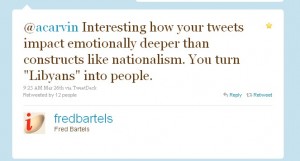

Most of mainstream news however, functions exactly in the manner feared, creating a playstation mentality to war and suffering. In that sense, Twitter news curation is the anti-playstation for wars. Or, as one of Carvin’s followers put it: