Egypt’s apparent move to shut off Internet has called for revisiting the so-called “dictator’s dilemma,” i.e. the idea that authoritarian governments cannot have their Internet cake and eat it, too. The dilemma is often framed as this: “If they allow Internet to spread within the country, it poses a threat to their regime. If they don’t, they are cut off from the world–economically and socially.”

China’s successful and widespread filtering of the Internet has caused many people to revaluate whether it was possible to allow the non-politically threatening parts of the Internet through while filtering out material that a regime finds objectionable. Notable, Evgeny Morozov argues that many people underestimate ability of dictatorships to impose a complex regime of filters and censors to keep the Internet from becoming a potential counter-force.

I would like to argue that the dictator’s dilemma is alive and well but, as with many other aspects of this debate, the reality does not lend itself well to simplistic analysis.

1- The capacities of the Internet that are most threatening to authoritarian regimes are not necessarily those pertaining to spreading of censored information but rather its ability to support the formation of a counter-public that is outside the control of the state. In other words, it is not that people are waiting for that key piece of information to start their revolt–and that information just happens to be behind the wall of censorship–but that they are isolated, unsure of the power of the regime, unsure of their position and potential.

2- Dissent is not just about knowing what you think but about the formation of a public. A public is not just about what you know. Publics form through knowing that other people know what you know–and also knowing that you know what they know. (This point was developed through a Twitter discussion with Dave Parry). Yes, all those parts of the Web that are ridiculed by some of the critics of Internet’s potential–the LOLcats, Facebook, the three million baby pictures, the slapstick, talking about the weather, the food and the trials and tribulations of life–are exactly the backbone of community, and ultimately the creation of public(s).

3- Thus, social media can be the most threatening part of the Internet to an authoritarian regime through its capacity to create a public(ish) sphere that is integrated into everyday life of millions of people and is outside the direct control of the state partly because it is so widespread and partly because it is not solely focused on politics. How do you censor five million Facebook accounts in real time except to shut them all down?

4- The capacity to selectively filter the Internet is inversely proportional to the scale and strength of the dissent. In other words, regimes which employ widespread legitimacy may be able to continue to selectively filter the Internet. However, this is going to break down as dissent and unhappiness spreads. As anyone who has been to a country with selective filtering knows, most everyone (who is motivated enough) knows how to get around the censors. For example, in Turkey, YouTube occasionally gets blocked because of material that some courts have deemed as offensive to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founding father of Turkey. I have yet to meet anyone in Turkey who did not know how to get to YouTube through proxies.

5- Thus, the effect of selective filtering is not to keep out information out of the hands of a determined public, but to allow the majority of ordinary people to continue to be able to operate without confronting information that might create cognitive dissonance between their existing support for the regime and the fact that they, along with many others, also have issues. Meanwhile, the elites go about business as if there was no censorship as they all know how to use work-arounds. This creates a safety-valve as it is quite likely that it is portions of the elite groups that would be most hindered by the censorship and most unhappy with it. (In fact, I have not seen any evidence that China is trying to actively and strongly shut down the work-arounds.)

6- Social media is not going to create dissent where there is none. The apparent strength of the regime in China should not be understood solely through its success in censorship. (And this is the kind of Net-centrism Morozov warns against but that I think he sometimes falls into himself). China has undergone one of the most amazing transformations in human history. Whatever else you may say about the brutality of the regime, there is a reason for its continuing legitimacy in the eyes of most of its people. I believe that the Chinese people are no less interested in freedom and autonomy than any other people on the planet but I can also understand why they have, for the most part, appear to have support for the status-quo even as they continue to have further aspirations and desires.

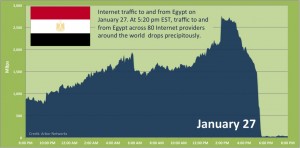

7- Finally, during times of strong upheaval, as in Egypt, dictator’s dilemma roars. The ability to ensure that their struggle and their efforts are not buried in a deep pit of censorship, the ability to continue to have an honest conversation, the ability to know that others know what one knows all combine to create a cycle furthering dissent and upheaval. Citizen-journalism matters most in these scenarios as there cannot be reporters everywhere something is happening; however, wherever something is happening there are people with cell phone cameras. Combined with Al-Jazeera re-broadcasting the fruits of people-powered journalism, it all comes down to how much force the authoritarian state is willing and able to deploy – which in turn, depends on the willingness of the security apparatus. Here, too, social media matters because, like everyone else, they too are watching the footage on Al-Jazeera. Their choice is made more stark by the fact that they know that history will judge them by their actions–actions which will likely be recorded, broadcast and be viewed by their citizens, their neighbors and their children and grandchildren.

P.S. Slightly edited, mostly for typos.