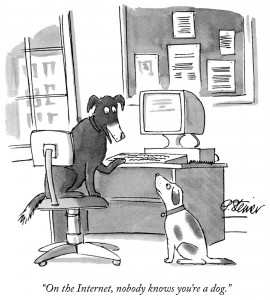

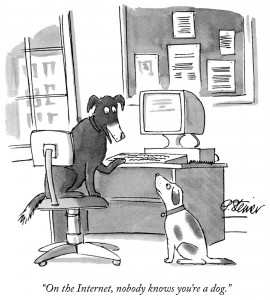

As the Internet first spread to the general public, there was great excitement about the potential identity experimentation. Gender, race, identity could, it seemed, all be re-invented online at the strike of a keyboard as, largely due to bandwidth limitations, text-based social environments dominated those days. Plus, unsurprisingly, the [smallish] community which owned computers and was willing to go through the cumbersome set-up of dial-up in order to investigate these new social environments tended to be somewhat atypical. As pioneers, it is probably safe to say that they included an unrepresentative large number of people interested in experimentation. Besides, it seemed all so novel. Thus, the most famous Internet cartoon was born:

“On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

To cut a long story short, and to say the least, this dynamic has been reversed. As the Internet became more and more accessible, as more and more ordinary people joined, as increasing bandwidth facilitated sharing of photos and videos, and as it all became mundane and domesticated, Internet has increasingly emerged as an identity constraining medium as it allows for surveillance and triangulation of information about a person like never before. In my 5+ years of research on Facebook use in college, this has become a dominant theme. Transitions and multiple audiences pose novel challenges; audiences which were separated by space (say friends in different colleges or parents) and receded by time (high school friends once you go to college) are increasingly all one’s Facebook friends and the privacy settings and controls do not make it intuitively easy to manage this massive complexity the way space and time helps us manage it in culturally-appropriate ways. Plus, these are not the only digital cookie crumbs we leave; through multiple services, social sharing sites, shopping sites, we increasingly reflect larger and larger parts of our lives in the digital domain, making it easier for someone to piece together who we are, at least somewhat, and for contradictions to be more glaringly evident. This, I had dubbed, grassroots surveillance but it goes by many names. I think I best like Nathan Jurgenson’s coinage: the omniopticon.

And this has real implications for people living under repressive regimes; especially if they are involved in any kind of political activity as hiding is more and more difficult. Under current conditions, it is more true to say that “on the Internet, everyone knows you’re a dog.”

Facilitating this level of surveillance is the fact that Facebook has a strict real-name policy in writing but it is relaxed in implementation because while Facebook has an incentive in making people use their real names, it seems to have no particular interest in kicking out everyone who choose, for whatever reason, to use nicknames or variation of names. (According to my survey of College students, that is at least 10% and likely a lot more considering variations of real names (i.e. FirstName MiddleName as Facebook profile name) and also likely a lot higher in other populations such as high-school students who have more concerns from parents, teachers and college admission boards. Generally, Facebook does not take down pages of even the most obvious nicknames and pseudonyms unless someone complains. Which, of course, means that the real name policy is most dangerous for people who are most vulnerable: those with enemies who will report them.

Enter Wael Ghonim. Ghonim had created a Facebook Page “We are All Khaled Said” in honor of the young man who was brutally beaten to death by the Egyptian police. As we now know, that page played a pivotal role in calling for the revolution in Egypt which started on Jan 25. Less well remembered is that the page almost went offline as Ghonim was using a pseudonym, “El Shaheed”, the Martyr. Someone, presumably the Egyptian state, complained. Facebook promptly took down the page and only restored it after Nadine Wahab, based in D.C., let Wael Ghonim use her identity, with her password and screen name, to administer the page. This may seem like a minor deal but this effectively meant that Nadine herself was perhaps forever exiling herself from her own country, or endangering family members who might still be in Egypt.

So, at this point, dear reader, you might be thinking I am about to continue with an impassioned plea for Facebook to allow for pseudonymity. That is not the case at all. I increasingly believe that the norm towards real(ish) names on Facebook has been a very fertile ground for dissent under autocracies. The close integration between online and offline persona which exists on Facebook is exactly the quality which makes Facebook very useful for reshaping the public sphere under undemocratic (and democratic) conditions; and the push towards real(ish) names helps further that integration.

But let’s now consider the case that is making the headlines, that of pseudonymous blogger Amina Araf (PS: “She” was later revealed as a hoax: here’s the Wikipedia page). As of this writing, we know that her real name is almost certainly not Amina Araf and that the pictures of her on her blog and elsewhere belong to someone else. We also know that her last blog entry was signed by a cousin, claiming she had been kidnapped. There is great consternation among people concerned with human rights in these countries; people are afraid that if this turns out to be a hoax, it will discredit future efforts to build person-to-person links and to raise awareness. On the other hand, what if everything but the name is mostly true, what if she is being tortured in a Syrian jail? Of course, we know for a fact that people are being tortured in Syrian jails regardless of what their names might be; however, it is true that it’s often politically important to have a representative, sympathetic face of repression to rally around—the so-called “panda” of the environmental movement. Rationally, insects and worms going extinct in large numbers are probably a bigger problem than if we lose the pandas who seem to be singularly unsuited to survival: they eat the some of the least indigestible foods short of rocks; they have a very short mating season and, worse, they need a lot of prodding as they seem particularly incompetent and uninterested in the activity. Still, they are adorable, especially as cubs, and WWF will use a panda as its symbol rather than a bee or another insect whose extinction would truly threaten our food supply whereas panda extinction would primarily threaten financial survival of zoos.

So, is Amina Araf the Panda of the Middle East Uprising? An eloquent, gay, out, dissident, attractive young woman who hits pretty much every note which appeals to broader Western publics? And imagine, now, that this Panda is partially fictionalized, as it certainly seems to be, or worse, a hoax, as has been suggested, or even worse, a trap by the state security system, as has already been raised? Frankly, if the last option is true, that this was a trap by the Syrian state to obtain identity information from activists who corresponded with her, I would propose that this really shows the stupidity of the regime because the real threat to an autocracy is not a few activists, who can certainly be detained but a sympathetic, eloquent figure like Amina whose writings about the repression in Syria certainly helped raise awareness abroad about the true nature of the regime. The most fatal threats to autocracies are widespread outrage among their public expressed in a manner visible to their public rather than any particular activist. Still, let us not discount any possibility however counterproductive it might be for the Syrian regime.

This brings me back to question of pseudonymity and Facebook. I certainly believe that there should be spaces, like Twitter and pseudonymous blogs which allow those in danger to express themselves while trying to minimize the repercussions. That said, there is no real safety in technology for activists and, ironically, there is more safety in numbers which the real name policy might actually help. Which means that we are increasingly headed for a future in which we try to both balance and protect pseudonymous spaces for activists, and risk the thread of hoaxes, traps and fiction, as well as identifiable spaces like Facebook, where people might put themselves in grave danger and within easy reach of the state.

First, there is no absolute safety in technology. The Internet is a notoriously unsafe system because it was designed that way; competent hackers are almost always one step ahead of most security systems and some of those hackers work for states and other shadowy organizations. Plus, in many autocracies, the state has access to the physical wire which tends to have a bottleneck under control of whatever the Ministry of [Information | Communication | Surveillance | Censorship | Propaganda] is called in that particular state. Yes, a very technologically-competent activist using the appropriate tools may be able to evade surveillance better; and yes, activists in such states should make it harder for the state to pick them one by one by using all measures available to hide from the state while online; and, yes, please technology companies, you should always implement the well-known safety precautions against hacking, phishing and “man-in-the-middle” attacks such as https, two-step logins and secure systems without the human rights community having to plead with you for such minimal protections.

All this to emphasize: there is no technologically-assured safety for a dissident in a repressive-enough regime. The only safety is visibility, public attention, sometimes international attention and numbers everywhere–in and out of the country. As I have been arguing, a state is a resource-constrained actor. It is not possible for an autocracy to remain stable and arrest a million people. They can certainly arrest a few; they can shed the blood of large numbers. However, the first option they can exercise while preserving stability; the latter requires destabilization which is not what most dictators are longing for. To get that safety in numbers, however, there needs to be political activity in spaces where there are numbers and where the regimes find it harder to flood the place with misinformation, trolls, “sockpuppets” –like the type apparently the Defense Department considered using in weaponized form, I kid you not—and the like. And both real names and online-offline integration guard against these threats and help provide numbers but at the expense of the safety of the activists.

This is a reverse tragedy of the commons. Tragedy of commons is when everyone does what is in their best interest, the commons suffers. (For example, if everyone cheats on their taxes, everyone gets hurts because crumbling infrastructure is bad for everyone). This is the opposite case: to raise awareness, to organize, to oppose regimes, activists are best directed to spaces where pseudonymity is fairly minimal and online/offline integration is high; which, of course, makes it easier for the state to find them. Thus, this is the tragedy of the individual and a reverse tragedy of commons; what is good for the commons is dangerous and potentially deadly for the activist.

Does this mean I support the notion that Facebook should have turned over Wael Ghonim to the Egyptian authorities and shut down the page? Of course, not. The biggest problem here is that Facebook has only a few thousand employees to manage a user base of 600+ million. When the ratios are like that, most processes are automated and peer-enforced. The 10+% nickname users in my sample of college students have fairly little to fear from Facebook deactivating their accounts; however, those most in need of protection have the most fear.

Also, Facebook seems torn. Back in spring, I listened to Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg boast to Naval College graduates, where we were both speakers during the Foreign Affairs Conference of 2011, about the role Facebook played in bringing about change in the Middle East. I understand that as a for-profit corporation, they are not necessarily most interested in their new-found role; however, I also understand that Sandberg may well be genuinely proud of the role her company played. Either way, this role is here to stay and Facebook has to develop policies to deal with it in a way consistent with human rights concerns. Besides, online networks are very prone to cascades where users can exit in mass numbers and Facebook exists by the force of the hundreds of millions of people who are willing to stay there. I am sure that they do not want to deal with an event in which Wael Ghonim of, say, Burma or another country, gets tortured to death because of Facebook policies or technological weaknesses.

There is no way for Facebook or any other company to deal with this in a completely automated fashion. Facebook needs to man up and woman up and devote larger, much larger, numbers of people to deal with complaints over real name and seriously consider “case by case” exceptions. I know that some of the executives might think that this will open the floodgates to “fakebooks” but as I am finding in my research, and as others will certainly find in the future, majority prefer to use their real name anyway; and many people are already not in full compliance with the TOS and this poses no threat to Facebeook. Facebook seems to have no problem with that as the online/offline integration provides enough of a grounding to make Facebook a core social network site for many people. There is a large human rights and technological community willing to work with Facebook (also Google– as gmail is a key platform for activists as well—and Twitter and others) to try to find our way through the 21st century in a way which is consistent with human rights. I am not going to write a blanket recommendation here because I think it is important to develop these policies in a broader dialogue; besides I don’t have ready answers.

Finally, the human rights community has to understand that allowing pseudonymous spaces which provide more safety for the individual will eventually create cases like that of Amina Araf where some or all parts of the person will turn out to be fictionalized. There will be hoaxes. There will be traps. On the other hand, there will also be brave, human voices who will blog or be active online pseudonymously under grave danger and then emerge under freedom as we saw with the case of Wael Ghonim and others. Whatever the specifics of the Araf case turn out to be, the danger and repression is very real and there is real value in preserving safer, pseudonymous spaces for activists. On the other hand, as we have seen in Tunisia and Egypt, sometimes less safe spaces such as Facebook provide greater political efficacy for the political cause at the expense of safety. Activists everywhere already weigh these considerations as they brave possibility of death and torture; I won’t bother with platitudes to their undeniable courage.

However, the world owes these people both the best chance to hide as well as the optimal conditions to not hide; to that end, technology companies must sit down with human rights groups and others to figure out best ways to navigate this complexity while the human rights community and all concerned citizens must not let their hearts and trust be destroyed if, inevitably, hoaxes and other complicated cases emerge. Safety, anonymity, trust and political efficacy have no perfect intersection, no optimal solution, no sweet spot. It is all compromise, judgment and balance. Even as the tragedy of the individual gives rise to the benefit of the commons, we must do our best to provide these individuals with maximal space and options to configure this impossible puzzle as they best judge as ultimately, these decisions are on their shoulders as is the price to be paid.