Many commentators relate the diffuse, somewhat leaderless nature of the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia (and now spreading elsewhere) with the prominent role social-media-enabled peer-to-peer networks played in these movements. While I remain agnostic but open to the possibility that these movements are more diffuse partially due to the media ecology, it is wrong to assume that open networks “naturally” facilitate “leaderless” or horizontal structures. On the contrary, an examination of dynamics in such networks, and many examples from history, show that such set-ups often quickly evolve into very hierarchical and ossified networks not in spite of, but because of, their initial open nature.

This question has been raised here by David Weinberger who asks the question, and, here, by Charlie Beckett who argues that the diffuse nature of these networks makes them less hierarchical and stronger:

The diffuse, horizontal nature of these movements made them very difficult to break. Their diversity and flexibility gave them an organic strength. They were networks, not organisations.”

I agree and have said before that this was the revolution of a networked public, and as such, not dominated by traditional structures such as political parties or trade-unions (although such organizations played a major role, especially towards the end). I have also written about how this lack of well-defined political structure might be both a weakness and a strength.

A fact little-understood but pertinent to this discussion, however, is that relatively flat networks can quickly generate hierarchical structures even without any attempt at a power grab by emergent leaders or by any organizational, coordinated action. In fact, this often occurs through a perfectly natural process, known as preferential attachment, which is very common to social and other kinds of networks.

In order to understand how this process works, consider the potential mechanisms by which a node in a network grows in importance. Let’s do a short-hand conceptualization and accept the number of followers in a Twitter network as a measure of importance.

Followers may increase through any of the following mechanisms:

1- Random growth: Here, we can assume that everyone gets some number of followers every time they tweet and that it all averages out over time. Nobody has any particular advantage and over time, most everyone acquires some followers, although some more than others. This is analogous to the movement of gas molecules in containers: they all bounce around in a way that is impossible to calculate, but important parameters (like temperature) can be calculated very accurately as averages. Random does not mean without a pattern–this would not mean it all end ups with everyone as equal but rather with a Maxwell-Boltzmann-type distribution. For a fascinating study of how the bulk of the economy (except for the very rich) function in this manner, see this paper by Victor Yakovenko .

2- Meritorious growth: In this model, the better, the more relevant, the more informative your tweets, the more followers you get. Surely, there is a lot of this going on. While this sounds good, it brings us to the next question: how will people know your tweets are so good? One mechanism, of course, is retweets. The number of retweets, however, may depend on how many followers you have to catch and retweet your posts in the first place. This means that those who have a large number of followers end up with an advantage even in terms of being recognized as meritorious. (Recent studies do show that influence is a lot more complicated than number of followers, but we are trying to abstract some basic mechanisms, so this will do for the moment).

3- Preferential attachment: This is the “rich-gets-richer” model, sometimes dubbed the “Matthew Effect” after the biblical saying “For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.”

In the preferential attachment scenario, the more followers you have, the more followers you will add, ceteris paribus – i.e. even if the merit of your tweets is the same as someone of fewer followers, your followers will grow at a faster rate. Multiple mechanisms can facilitate preferential attachment — this need not be a mere exposure effect but will likely be confounded by a popularity effect. In almost all human processes, already having a high status makes it easier to claim and re-entrench that high-status. Thus, not only will more people see your tweets, they will see you as having the mark of approval of the community as expressed in your follower count.

This third kind of process, defined by preferential-attachment dynamics, tends to give rise to what network scientists call “scale free” networks, which end up exhibiting power-law distributions. (They are scale invariant because they look the same at whatever scale you look at). Sometimes informally-called the 80-20 networks, such networks are very common in multiple natural and social processes and create top-heavy structures in which a few have a lot and most have fairly little. (See this related paper by Yakovenko for an analysis of how the rich really are different than you and me in that their wealth indeed accumulates by power-law dynamics. They really are getting richer because they are rich to begin with).

Many networked structures, including the World Wide Web, have been shown to be such scale free networks (See this paper by Adamic and Huberman in Science for an interesting discussion which also touches upon the merit aspect). More importantly, blogs and other influence-ecologies of the Internet often display such a shape. Here’s what a power-law distribution of blogs looks like from Clay Shirky’s widely-read post on the topic (this is a bit outdated, if anyone wants to generate a new one using Technorati’s top 100, I’ll happily include that one instead):

So, what does all this have to do with revolutions and leaders? A lot, it turns out. Preferential attachment means that a network exhibiting this dynamic can quickly transform from a flat, relatively unhierarchical one to a very hierarchical one – unless strong counter-measures are quickly and firmly employed. It is not enough for the network to start out as relatively flat and it is not enough for the current high-influence people to wish it to remain flat, and it is certainly not enough to assume that widespread use of social media will somehow automatically support and sustain flat and diffuse networks.

On the contrary, influence in the online world can actually spontaneously exhibit even sharper all-or-nothing dynamics compared to the offline world, with everything below a certain threshold becoming increasingly weaker while those who first manage to cross the threshold becoming widely popular. (Imagine Farmville versus hundreds of games nobody plays. In fact, don’t imagine this and read this great study by Jukka-Pekka and Reed-Tsochas that was just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Turns out that’s exactly how app diffusion on Facebook works).

First, let me say that many late-20th century uprisings which predate the Internet happened without strong leadership so a “leaderless revolution” is not a new phenomenon. Iran in 1979 did not start as a theocratic movement at all—the despotic and unpopular Shah was overthrown by a broad-based movement including the secular middle-classes, organized labor, communists, etc. Many of the 1989 revolutions did not have strong leadership as they were happening. My initial impression is that the Egyptian and Tunisian uprisings have been even more diffuse and that this is related to the role social media played in facilitating certain kinds of organizing—but I am willing to remain agnostic on that question till we have more data.

However, few revolutions remain leaderless—which is exactly why it is very important to understand that the diffused nature of this revolution is hardly an inoculation against the emergence of this dynamic; in fact, it might even contain the seeds of extreme hierarchy

To try to understand whether this might be happening in Egypt, I used this “infograph” –which is, in fact, visualization of a social network analysis of Twitter users employing the hashtag “Jan 25”—to identify some of the more influential nodes. (In this graph, influence is visualized as size; the bigger, the more influential) Not having the underlying data, I eyeballed the graph and asked my twitter friends for names of Egyptians with an influential social media presence.

Thus, while my final list is somewhat arbitrary, let me assure you that I tried many variations of this top 10 out of the potential few hundred and constantly found the same pattern. In the one I present here, I’ve included male as well as female micro-bloggers, those tweeting in only Arabic as well as those tweeting in English and Arabic and two traditional politicians, Ayman Nour (@ayman_nour) and Mohamed El-Baradei (@ElBaradei). (Baradei was not included in the infograph but I added him due to his obvious importance. I tried to check for other potential figures as well, none were as prominent).

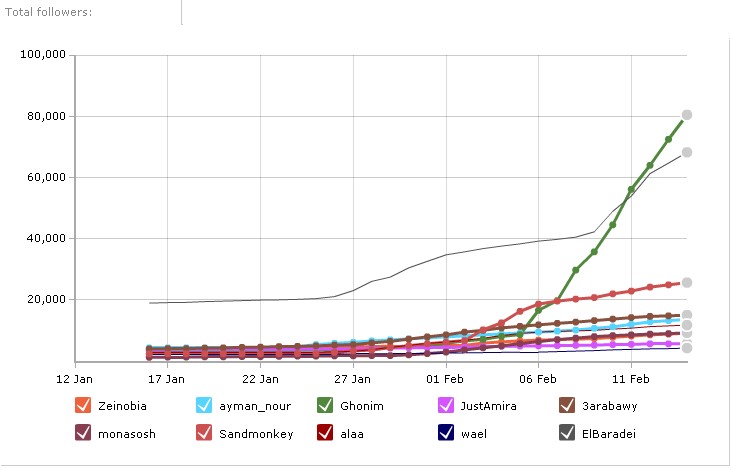

What I found is that @ghonim, or Wael Ghonim, and @ElBaradei, Mohamed El-Baradei, are both definitely showing a different kind of growth-pattern compared to every other person of influence I have tested them against in this portion of the twitter-verse. Of course, you can see this pattern without any quantitative analysis; Ghonim is the one that has been crowned the “leader of the leaderless revolution” by Newsweek and he’s the one who is tweeting about meeting with top generals in the military. Take a look at his and Baradei’s follower growth compared to 10 other top tweeters.

By all accounts, Wael Ghonim deserves an important leadership role. I absolutely do not mean for this post to be taken as a personal assessment of any leader of this nascent revolution. In fact, the point is that it does not matter who they are. Wael Ghonim especially has been careful to talk about how this is a revolution without heroes because so many are heroes—starting, of course, with the hundreds of people who lost their lives. He has dubbed the Egyptian uprising “Revolution 2.0” and has constantly talked about keeping it participatory, especially through the use of social media.

However, Ghonim and other emerging leaders of this revolution would be well-advised to keep in mind that social media not only do not guard against one of the strongest findings of sociology called the “iron law of oligarchy,” they may even facilitate it. The iron law of oligarchy works rather simply. Basically, take an organization. Any organization. Stir a bit. Wait. Not too long. Watch a group of insiders emerge and vigorously defend their turf, and almost always succeed. (Example one could be Western democracies — See work by Robert Michels for more details). Further, revolutions almost always depend upon or create figures who possess what sociologists call charismatic authority. Both of these processes are so widespread in human history that it would be foolish to ever discount them. But to discount them by hoping that social media, as it stands, can provide a strong-counter force would be naïve.

In fact, if anything, it is quite likely that preferential-attachment processes are part of the reason for the rise of oligarchies and charismatic authorities. Ironically, this effect is likely exacerbated in peer-to-peer media where everything is accessible to everybody. Since it is just as easy to look at one person’s twitter feed as another’s, no matter where you are or where the other person is, it is easier to draw more from the total pool and further entrenching an advantage compared to the offline world where there are more barriers to exposure and attachment. Thus, networks which start out as diffuse can and likely will quickly evolve into hierarchies not in spite but because of their open and flat nature.

Disposition is not destiny. In one of my favorite books as a teenager, The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Leguin imagines a utopian colony under harsh conditions and describes their attempts to guard against the rise of such a ossified leadership through multiple mechanisms: rotation of jobs, refusal of titles, attempts to use a language that is based on sharing and utility rather than possession and others. The novel does not resolve if it is all futile but certainly conveys the yearning for a truly egalitarian society.

If the nascent revolutionaries in Egypt are successful in finding ways in which a movement can leverage social media to remain broad-based, diffused and participatory, they will truly help launch a new era beyond their already remarkable achievements. Such a possibility, however, requires a clear understanding of how networks operate and an explicit aversion to naïve or hopeful assumptions about how structures which allow for horizontal congregation will necessarily facilitate a future that is non-hierarchical, horizontal and participatory. Just like the Egyptian revolution was facilitated by digital media but succeeded through the bravery, sacrifice, intelligence and persistence of its people, ensuring a participatory future can only come through hard work as well as the diligent application of thoughtful principles to these new tools and beyond.