#FreeMona

It was a calm, quite night, almost nine o’clock, on the eve of Thanksgiving holiday when, out of the corner of my eye, a tweet shook me:

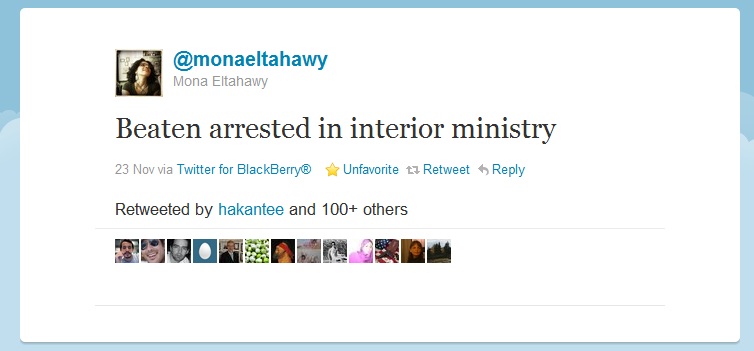

Egyptian-American writer and my friend Mona El Tahawy, who had cut her trip in North Africa short to join the exploding Tahrir protests in her native country, had just sent that out. Short, uncapitalized, clearly written in a hurry. And with that, she went silent.

As a scholar and a concerned citizen, I had been following Egypt’s revolt closely. I knew that the security apparatus in Egypt had, in some ways, grown even more arbitrary since the ouster of long-term autocrat Hosni Mubarak after 18 days of intense protests in Tahrir. About 12,000 civilians had been detained and were subject to “military trials”. Since the eruption of new protests, at least 35 protestors had been killed and thousands injured. A few weeks ago, a prisoner, Essam Atta, had been tortured to death in prison.

At worst, Mona’s life was in danger. At best, she would likely be subject to beatings, sexual abuse.

As I stared at the tweet as my mind raced back to my conversations with Mona about her days in the American University of Cairo and her lifelong, outspoken opposition to Egypt’s autocracy. Because she was a Guardian columnist, a prolific tweeterer and a public speaker, she was identifed with the Egyptian uprising by many. She would certainly be in trouble with her country’s military rulers.

Her tweet stream indicated that she was near Mohammed Mahmoud street, where clashes had been going on for days between protestors and CSF, the paramilitary police. Most likely, I thought, she was apprehended by people who did not know of her global standing, but saw her as a woman out in the street late at night involved in protests–and I knew this too would be a big danger to her. Soon, though, mid-level higher-ups would discover that she was relatively well-known–and her treatment from then on would likely depend on public reaction to her arrest–both in Egypt and globally. Prominent Egyptian activist and my friend Alaa Abd-el Fattah, who is now in prison under the military trials regime, was also arrested in 2006 and spent six months in Mubarak’s jails. Alaa later stated that the global campaign to free him probably caused him to spend more time in prison, as the regime realized they had a valuable target, but also spared him from torture.

When activists are arrested, in some cases, it is best to keep it quiet. In some cases it is best to kick up a big storm. Worst option, however, is to kick up a small storm which irritates the powerful, but without enough strength to nudge them to action. Considering the options, I thought Mona needs the latter, and probably cannot be quietly freed anyway. As a woman, she’s in danger from the low-level police who now have her at their mercy. She needs to be plucked out of there, and that requires high-level intervention. As a prominent dissident, she is in danger from those higher-ups who might want to make an example of her the way they are currently doing with Alaa. Mona needed a huge campaign which made it costlier to keep her than to release her.

A few decades ago, contemplating launching a global campaign like this would require that I own, say, a television station or two. I hadn’t even unpacked my television set when I moved to Chapel Hill to take up a position as an assistant professor in University of North Carolina. Heck, I dodn’t even have a landline phone. But, “I” wasn’t just an “I.” Due to my academic and personal interests, I was connected to a global network of people ranging from grassroots activists in Egypt to journalists and politicians, from ordinary people around the world to programmers and techies in Silicon Valley and elsewhere. My options weren’t just cursing at a television set –if her arrest had even made the news in the next few days. I could at least try to see what *we* could do, and do quickly.

Concise, fast, global, public and connected was what we needed, and, for that, there is nothing better than Twitter.

I immediately reached out to Andy Carvin, NPR journalist extraordinaire who’s been covering the Middle East uprisings, and a friend of many years going back digital divide efforts, a topic which I’ve long studied as a scholar. I was very happy to see he was online and, of course, similarly aghast at Mona’s situation.

One challenge of new media environments is that they scatter attention and consequently tools and channels which can unite and focus attention are key to harnessing their power. Hashtags and trending topics are one way in which people can focus among the billions of tweets floating in cyberspace. In fact, a key dynamic in “social media” is that it works best when coordinated with “focusers”: trending topics, Al Jazeera, Andy Carvin (whose stream is widely followed) are all focusers, albeit very different ones (Well, one is a satellite TV channel, one is a cool guy with a very cute, huge dog, and the last one is an algorithm). Hence, the “Occupy” movement was deeply disappointed when Andy Carvin did not cover them, as his beat was Middle East, and as he already works about seven days a week. Occupy activists knew that without Carvin, they had lost a potential focuser. (Police brutality and overreaction solved that problem for Occupy movement by garnering traditional media coverage which served as a crucial focuser).

So, first, I knew we needed a hasthag. A focuser.

Wanting a short one due to Twitter’s character limits, I proposed “#Mona”. Andy quickly checked and realized that it was already in use and suggested “#freemona.” I tweeted out an agreement and opened a column in my Tweetdeck to check only tweets tagged “#freemona”. In about a minute, the column started flowing too quickly for me to read everything.

20 minutes later, #freemona was trending worldwide.

Ok, that’s the global campaign, I thought as I marveled at how quickly it had taked off with barely a nudge. In the pre-social media world, it might have taken weeks and a lot of luck to achieve even a sliver of such awareness globally.

But that wasn’t the only leg of our frantic, crowdsourced efforts. @Cairowire, curated by @sarahbadr, contacted the US Embassy — and informed us of this fact on Twitter so we could avoid flooding them with calls. She live-tweeted her call so we could provide as accurate information as we knew in response to questions from the Embassy. Was she a US citizen? I knew she was, and others chimed in. Where was she seen last? What was her birthday? I looked it up and answered. Who was she with? People chimed in with what they knew. @Cairowire told us the embassy had taken down the information.

Many times, the most dangerous moment for a dissident or an activist is the police station where low-level functionaries can have impunity to do the worst. The combination of her gender, personality, citizenship and her role as a media person was a very dangerous mix for that “police station” phase. We needed to try for very high-level intevention to pluck her out–and it was almost 4am in Cairo and a holiday in the United States.

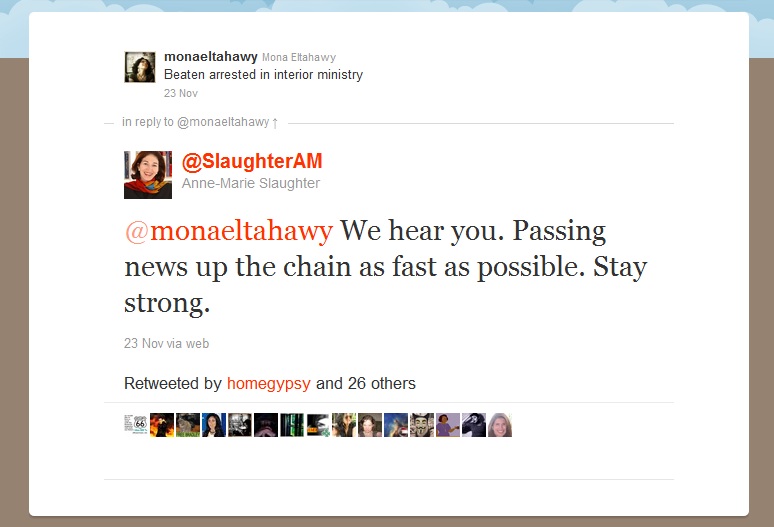

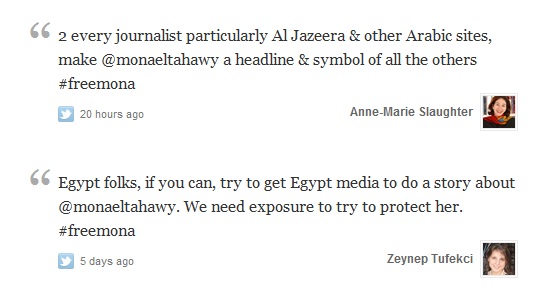

With very similar thoughts –and we were constantly conversing–, Andy Carvin and I both reached out to Anne-Marie Slaughter, prominent Princeton professor and former advisor to Hillary Clinton. She’s probably better known to most people as Twitterer extraordinaire, @SlaughterAM where she can be regularly found mixing it up with high-level politicians, activists, ordinary people around the world. To my relief, she was online. She jumped to action. Soon, she reported that she had reached out to her contacts at the State Department, and that this was being dealt with at the highest levels as the urgent situation it was:

Egyptian activists on the ground, who had been organizing against the arbitrary arrest and detentions, were best placed find her and to provide her with legal and other resources. Cairo never sleeps, and, sure enough, many of them were online. Shahira Abouellail, @fazerofzanight, who works tirelessly with the no military trials campaign responded quickly and informed us of the likely sequence of events, places she might be at and that she would make sure that lawyers would start looking for her early in the morning. (In fact, all through last week, Shahira had been talking about all the people being detained, beaten and abused as the protests grew).

A similar outreach effort was launched, especially to the tech community, to see if Mona’s tweets, or tweets of people we thought might have been arrested with her, contained geolocation information which was available to Twitter (as storified by @katz):

Soon, though, that turned out not to be the case (although that had been essential in confirming the arrest of Slim Amamou, for example when Slim “checked in” at the Ministry of Interior in Tunisia during the protests.)

Finally, at the same time, global media had started picking up on Mona’s disappearance. I urged my Egyptian tweeps to contact local media as exposure can sometimes be the best protection for a dissident as storified by@katz):

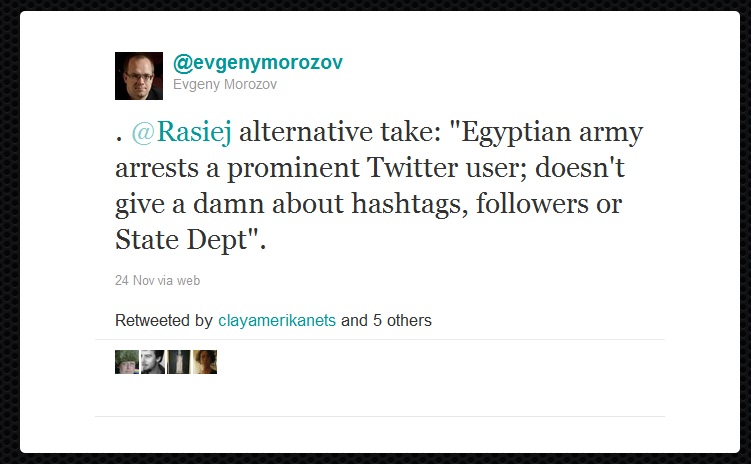

Many people misunderstand the power of publicity on repressive regimes. Just because the power of a state is relatively unchecked by institutional balances does not means that it has infinite repressive capacity, or that it is unconcerned about public opinion. All regimes, even the most repressive ones, are concerned about legitimacy and appearances. In a debate with Andrew Rasijej, Evgeny Morozov tweeted the following:

This, of course, is naïve. Egyptian army absolutely gives a damn about social media. You only need to notice that they have their very own Facebook page and release their “communiqués” solely through Facebook.. Why? Because, like all repressive regimes, they realize that their power rests not just on coercion, but also a degree of legitimacy and acquiescence among the public–and the public sphere increasingly incorporates networked citizenry on social media. Hence, they are there where they rightly perceive many Egyptian activists and citizens are. In the 21st century, no regime worth its salt will ignore social media; those who do will find themselves looking for places to retire.

In fact, I know of no better proof about the power of social media to potentially empower dissent than the numerous anecdotes in Evgeny Morozov’s book about the extraordinary efforts authoritarian regimes go to suppress, control and censor social media. If it were actually irrelevant, they would have happily ignored it. Instead, they are on full-alert, attempting to fight social media on all cylinders.

It’s also naïve to think that the Egyptian army does not give a damn about the State Department, especially when it comes to releasing activists. SCAF, like all repressive apparatus, makes calculations about costs and benefits–and keeping a prominent journalist in detention becomes more costly when combined with a global publicity campaign, State Department pressure, Egyptian activists, as well as local and global media coverage.

Of course, such global campaigns also play a role in how State Department acts. State Department is the foreign policy arm of the most powerful country in the world and, as such it will act according to what it perceives as the foreign policy interests of the United States. However, global campaigns can make it harder for foreign policy interests of the United States to align with supporting repressive regimes. (I personally and strongly believe that the true and long-term interests of the United States also lie in this direction and that historians will look at its support for repressive regimes as colossal mistakes). I believe that social media can help us organize to make sure big governments are pushed to do the right thing. Besides, State Department, like any other institution, is composed of people and I am sure some of those people would rather help do the right thing. “The Whole World is Watching” is such a resonant slogan for a reason.

So, it was a perfect storm. A global social media campaign, institutional power, grassroots Egyptian activists, network-savvy global players and traditional media converged upon Mona El Tahawy’s case. It had been merely a few hours and I thought that all that we could do was done. People on the ground were aware and mobilized, global media was covering the event, official attempts were being undertaken, and a global conversation of concern was taking place in the still dizzily flying #freemona column on my monitor. I went to bed, still buzzed from the frantic activity but in need of some rest.

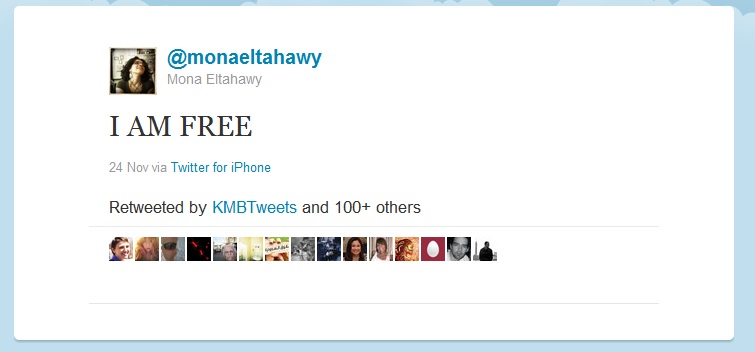

After a few hours of restless sleep, I woke up and immediately checked my Mona’s twitter feed. It beamed, “I AM FREE”:

Sexually assaulted, beaten, arms and hands broken, but in high spirits, she was out. Through broken bones, she detailed her ordeal first on Twitter, and later on CNN, BBC and Egyptian local media and beyond:

Social Media’s Role: Untangling Causality in Social Science

Was she freed because of the global campaign? While it is always important to carefully consider the evidence, in social science, always beware of people who automatically say “But you haven’t proven it!” because that shows they either don’t understand how social science works, or they do and they are disingenuous and are seeking argument for the sake of argument or attention. That’s just now the way it works in social science.

To put it bluntly, there is no way to conclusively prove anything in social science simply because we cannot do real experiments. (Take the identical person, place them in an alternative universe under equal conditions except social media and see how it would evolve. You see the problem: no alternate universe, no time machine, no cloning technology). So the question is never “did you prove it” but rather “what’s the evidence, what more data can we bring to this question, what’s our conceptual model and is it convincing?”

Social scientists do advance knowledge. As always, the more data the better. However, almost always, data remains suggestive and associative (it seems more of X was associated with more of Y). In order to understand a dynamic, we also look at causative mechanisms, narratives, comparative cases and limits — what’s missing and not happening as what’s not happening can be as useful.

Good analysis in social science also requires good theoretical understanding which basically means correctly conceptualizing the dynamics in play. Start wrong, and you aren’t going anywhere.

Most important conceptual point is this: The idea that “social media does help make X happen” DOES NOT mean it was just social media–because that is a theoretical stance which views social media as not part of this word. In fact, critics of social media often fall into this trap as they keep repeating “it wasn’t just social media” as if that were a valid criticism. To state “it wasn’t just social media” is a mere and trivial description of the world, not an analysis of dynamics of how social media plays a role – was it big or small? Was it crucial or trivial? What were the pathways?

“It wasn’t just social media” is not a refutation because as stated, that sentence is devoid of cognitive content.

This theoretical stance is also why I try to avoid terms like “virtual” because it suggests something “not real”. Social media is “real”, as real as anything else out there. Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey call this “augmented reality”. I prefer to call it just reality.

The interesting question is, always, what role did social media play in altering dynamics of an event? And at first level of abstraction, the answer is often, yes, social media played a role because it is now an increasingly integral and important part of communicative infrastructure, part of the formation of the public sphere, part of networked activism, and part of everyday life. In the 21st century, it will be increasingly impossible to do political analyses without discussing social media dynamics as an integral part of the story.

You cannot tell the story of the Arab uprisings, for example, without including the story of the role of social media. Again, though, that is obviously not the only dynamic–how could it be? As Clay Shirky nicely explains here, when people say “Social Media did X”, they mean that it played an important role because that is how the English language works. When we say, “A person was shot by a gun” we don’t mean “the gun got up and shot the person” (well, not yet anyway as robotics may change that); rather, we mean that “someone pulled the trigger and that it is important that the weapon was a gun” –a lot more lethal–than say a pointed stick –much less a danger–or a knife– still dangerous but slower and often more survivable. Hence, the full story of the Arab uprisings will include determined activists, labor unions, human-rights advocates, ordinary people, Facebook and Twitter, protests in Tahrir, dissension within the elites, United States and other governments and many other factors. But, it doesn’t include everything so this is not a laundry list. Sword fights, for example, were not part of the equation in the Arab Spring as they would be if it were an uprising in the Middle Ages.

So, to conceptually analyze the role of social media in Mona’s case let’s look at what it did do, as well as comparative cases of its limits and challenges.

Social Media and Dynamics of a Global Campaign

1- Speed. Social media speeds up everything.

Without social media, so many people wouldn’t have known so quickly that she was arrested, beaten. With one tweet, she reached out to tens of thousands of people all at once. In the past, there would have been a response, but it would likely have been much slower. A campaign by Amnesty International in the old days might take days to organize, especially during Thanksgiving. And “slower” and “faster” are just not the same dynamic for multiple reasons. In other words, something faster doesn’t give you what something slower would give you, just quicker. It results in a different conclusion. Faster is different.

2- Social media allows for complex, diverse ad hoc networks to come together:

I cannot fathom getting a such diverse group of people ranging from journalists to Egyptian activists to State Department officials responding to the same situation, in a coordinated fashion, so quickly, without Twitter (and a few emails. It was almost all Twitter). Even simple questions can be a nightmare to organize. Who will call the embassy? What’s her date of birth? Who’s arranging the lawyer?

3-Social media is integrated in an increasingly global, networked public sphere:

Once again, people from Japan to Brazil to Australia to China talked about her disappearance. There is simply no analog to such grassroots-powered intervention in the public sphere, at a global level at that, pre-social media. Yes, it is not one big happy family but it is a level of integration that simply was not there a mere decade ago. Along with all the fractures, divides, inequalities, and conflicts, a networked public sphere has emerged. And it is global.

4-Social Media fosters personal interaction:

Because Mona was a prolific tweeter, she had interacted personally with many people in the past and that was probably important in her visibility. Before days of social media, she would be just a face on a newspaper column–still powerful, but not as personal. And personal connections matter deeply for human beings. And, yes, personal connections can flourish online as well as online/offline. She wasn’t just a face or a columnist or a public speaker– she was Mona to tens and tens of thousands of people.

5- Social media works for prominent people better (rich get richer):

Social media, like almost new tools, can differentially empower the already connected (rich get richer) as opposed to the completely or weakly unconnected. There are 12,000 people who were detained by military prosecutors in Egypt and many languish in jails without such attention.

However, this is not an either/or situation. Whether or not #freemona and #freealaa help others depends on whether they become “charismatic megafauna” –where a prominent example helps the whole ecology– or part of a “celebrity system”–where a few people get the attention in isolation.

Charismatic megafauna is how ecologists refer to popular animals such as the Panda or tigers–powerful symbols which help move people to preserve vast amounts of landscape. Ecologists aren’t just interested in playing with cuddly panda or tiger babies, and would like to save the whole ecosystem — but carefully and deliberately put faces of pandas and tigers on their campaigns because of the the way human brain and human societies work. It is just very hard to move large numbers of people without powerful and sympathetic symbols.

Mona and Alaa are both such powerful and sympathetic symbols and they are both aware of this. In spite of the fact that his wife is about to give birth to their first child, Alaa refused deals which would have gotten him released if only he would accept a few limits on his speech because he realizes the powerful symbolic position he occupies. In her very first interview, Mona immediately talked about her fellow detainees and how those less privileged than her face much worse fates. Still, though, it is not just up to their efforts whether attention bestowed only upon them. Activists and concerned people must be cognizant of this fraught negotiation between using the power of the spotlight on one person versus using it shine it on wider swaths.

This can’t be done just by complaining about the “celebrity” or “star” system as not only is that not going away (because it is a deep human impulse), and it is often the best way to start a campaign. The problem is making sure it doesn’t stop there–and that remains an open question and constant struggle.

6- Personal networks, unsurprisingly, remain the underlying key anchors of the global social media networks (hubs matter and hubs tend to be dense and interconnected among each other):

The strength of personal networks is in social movements and campaigns unsurprising. However, the point needs to be made explicitly because so many people still talk about “social media” as something virtual, or something “not real”. My observations and studies from the Arab Uprisings show that most of the key “hub” activists had deep personal connections among each other – connections which often started on social media, sometimes migrated offline, sometimes did not–but were nonetheless strong and deep. In other words, “strong ties” are important: the fallacy is thinking these ties are not aided by, or sometimes solely lived through social media. Such personal, powerful but relatively small networks also raise important questions about how things might have been different if either Andy Carvin or Ann Marie Slaughter were mashing sweet potatoes instead of being online that night? (The answer isn’t an automatic “totally different” as dynamic networks can both exhibit “hub-and-spoke” structures and replace “hubs” quickly if one is taken out. Still, the question is an important one to consider)

7- Traditional big interests remain powerful and, along with dynamics of the attention economy, social media cannot overcome all obstacles (Bahrain. Bahrain).

Egypt and Tahrir have managed to capture the world’s heart and interest. The ongoing protests in Bahrain –a smaller, less-populated country where U.S. and Saudi Arabia have much deeper entrenched interests and somewhat more complicated by ethnic tensions– remains mostly off the radar in spite of prominent online organizing and broad participation in protests.

That is not to say that social media played no role (it almost always plays a major role) in the Bahrain’s protests. In fact, most of the country is online and the battle for legitimacy is raged both online and in the streets. Without the Internet, the opposition in Bahrain may have never managed to organize and mount such a campaign. With the Internet, it can mount such a campaign but cannot overcome the limits of being a small country in the world’s oil-producing region, hence very big interests aligned against it. (As this story is ongoing, it remains to be seen how it all plays out). I would still argue that social media has made it harder to suppress Bahraini citizens’ aspirations for more democracy and participation. A more complex case is unfolding in Syria (not going into that as this post is long enough) where lack of organized dissent before the uprising makes it very hard to use social media to organize.

8-Just like pre-social media, it remains easier to organize for “no” harder to organize complex discussions:

Again and again, social media have proven very useful in organizing single issue campaigns “Down with X” or “Release Y” but it is a lot more complicated to organize a complex course of action. This, of course, is not a feature of social media but a feature of life — a “no” is more simple and only requires agreeing to a single point whereas the space of all possible versions of “yes” is vast and complicated. Social media does not magically solve this problem. Wikipedia is a very important example in this regard, both to understand the possibilities (pretty useful, fairly accurate entries are produced most of the time) and the limits (Wikipedia is a high-conflict, mostly-male environment with powerful “wikignomes” who wield a lot of power.)

In the end, did the #freemona campaign help free Mona? My conclusion is that it quite likely played a key role, as analyzed in the above multi-layer mix. Without a social media campaign, she might have languished in jail for days or months the way thousands of people on whom such attention is not bestowed in Egypt are languishing in jails. As a U.S.-Egyptian dual citizen, as a columnist, as a prominent social-media personality, and as someone with many personal connections who could be mobilized to help her, she was well-positioned to be helped by these efforts. I also don’t doubt that the attention her case is getting will help bring more attention to the problem of arbitrary detentions, arrests and military trials in Egypt – again, compared to a pre-social media world where there would be zero to no attention, this is a massive step forward. (Added: By no means this is enough–I am comparing with the past rather than making a normative statement).

As always, though, a complex mix of causal factors, from protests in Tahrir and elsewhere in Egypt to international geopolitics will structure the future of Egypt. It is also clear that the networked public sphere is now an integral, causal dynamic in this multi-dimensional, multi-causal system. This makes it even more important to move beyond trivial denounciations –“it wasn’t just the social media”– to a deeper understanding which looks at specfic actors, dynamics, networks and beyong to understand, and also, to change this world.

PS. Edited the evening of Friday, Nov. 25 to correct typos, add links, and slightly clarify a few sentences which were missing words. May continue to edit for typos and for adding links. On Monday, November 28th, I added a few more tweets using the excellent storify by @katz which can be found here.

you said it all… let’s hope more and more people get to understand the dynamics involved and the importance of social media in dealing with issues concerning the masses especially when it comes to grassroots organisation.

“‘It wasn’t just social media’ is not a refutation because as stated, that sentence is devoid of cognitive content.”

I disagree. “It wasn’t just social media” implies that social media was at least in part a cause of the outcome.

It is when used as a refutation to “this is how social media played a role.” It is merely repeating the same content, hence adding none.

Completely not the time for such an article, neither reflects the majority of protestors whose sole method of communication is word of mouth, the likes of Mona r bilingual, with modern phones with social networking apps, check the other 99% of protestors throughout Egypt and the middle east

i learned much about how inbred is the nature of the the academic conference-going twitterati set from this event

Thanks for this thoughtful post, and I’m very glad Mona was released and emerged in high spirits despite the ordeal.

A few thoughts, hopefully coherent.

I’m not easily convinced of the central importance of online communications in general and Twitter in specific in this type of event. There is a strong argument to be made that Twitter was used on this occasion; after all, it all started with a tweet from a habitual user of the Twitter medium. Twitter use was also clearly the mode of coordination for this campaign and effort, and the rapid emergence of this ad hoc organization would seem to have been directly facilitated by the global, instantaneous, and hashtag-able nature of the medium.

The trouble comes with the (for me inexplicable) desire to attribute causal roles to concepts like “social media.” A focus on how technology is part of events is a great corrective to ideas that would dismiss artifacts as mere context or setting. The insistence that what we do online is part of real reality and nothing virtual at all is equally important. But the hazard (as Evgeny has often written) of a focus on technology across different kinds of events is that the analyst risks losing her or his loyalty to the event or case itself.

One way to think about this is to imagine how the story would be written by someone in your position who happened to study elite political and news media networks rather than technology and society. The story would certainly include Twitter, and it would likely look very similar to the first half of this post, but there would be less focus on the mechanics of hashtag selection. Instead, we might hear more about the counterfactual that you mention about Anne-Marie Slaughter being unreachable. We might hear more about phone-calls to Foggy Bottom and concerns about preferential treatment. This story would also be interesting, but the technology would be a player rather than the whole play. The causal role of friends in high places might serve as the rejoinder. At some point, a multi-causal explanation of a single case just becomes a narrative. There’s nothing wrong with that, but what’s the need for causal rhetoric in such a case?

You make excellent points about speed, networks that emerge and operate through online media, and the fact that some things (like “it’s good to have friends in high places”) stay the same. Perhaps, though, the protests that it’s not all about social media come out of an honest concern that more traditional concerns such as power, leverage, etc., tend to escape notice when Twitter becomes a star.

So, in that spirit, some things I would love to hear more about (despite the fact that I have been a journalist and an academic on tech and society for several years):

Is there not something extraordinary not simply about reaching tens of thousands of potential viewers on Twitter but about the fact that tens of thousands of people all around the world actually care enough to follow distant events?

Has the online dissident campaign (thinking #FreeMona, Ai Weiwei, Chen Guangcheng) been part of a shift toward advocacy on heroes rather than on injustice at large, or is there more attention now to these things over all?

What is the role of ideological compatibility in which people get this extra attention, for instance comparing a pro-democracy activist who gains support and a land rights activist who gets no such attention despite great ambitions to improve the lot of impoverished communities?

Thanks again for an interesting read.

I’ve constantly said this, but let me take this occasion to repeat. There is practically no single-cause dynamic worth studying in the world (only the most trivial questions are mono-causal). For everything else, we have a complex mesh I call “networked-causality”–where everything interacts with everything else, all the time. And, there is no method by which you can talk about everything all at once. You must, by necessity, focus, which must, by necessity mean that other things are discussed in less detail.

So, what to do? I think the correct path is to incorporate and briefly note other relevant aspects when focusing on a particular element.

For me, the test isn’t whether a discussion concentrates on a particular aspect, but whether it is naive/wrong/ignorant of the whole context. In other words, concentrating on the way in which social media mediated this campaign is fine as long as one doesn’t, for example, ignore the pretty clear role State Department can play in a case like this (which, of course, assumes the US-Egypt relationship) and why this is so.

However, as important as it is to understand the *whole* context, I just won’t write 4000 words summarizing the history of US-Egypt relationship in this particular post. Heck, you’d need a book for that–and I wouldn’t even be the person to write that.

So, a worthwhile substantive criticism might be: “your background assumptions about US-Egypt relationships are wrong because xyz”- not “why aren’t you writing 4000 more words about US-Egypt relationship.”

Here, let me give one last example. I just said Mona was in danger at the police station due to her gender. I can write 10 bazillion words about gender in the Middle East. But then I can’t ever get to the rest of what I’m writing about. A good challenge would be to say, “no, you misunderstand, the Egyptian police tradition is to protect female detainees.” Not “why didnt you explain more about why her gender puts her in danger.”

So, if there is something you think I got wrong about the context, by all means, point it out (and that is how good scholarship advances).

Finally, I think it would be great if someone studying “study elite political and news media networks” wrote about the phone calls between Foggy Bottom and whatever they do in such cases. It isn’t, however, an alternative to what I wrote here. Someone should write that (and, they, too, would note that the public campaign impacted their actions) and I will write this aspect. Not either/or.

Graham writes “Perhaps, though, the protests that it’s not all about social media come out of an honest concern that more traditional concerns such as power, leverage, etc., tend to escape notice when Twitter becomes a star.”

This is doubtless the case for some of this sort of analysis, but certainly not all — some of it is designed to prevent certain sorts of ideas from being discussed.

Let me put the position to you as a counter-factual — start by assuming everyone were writing the story by analyzing political elites and news media. What would be an acceptable way of discussing the fact that both those elites and those media well predated the contemporary situation, while some of the forces at play were new? Wouldn’t you have to do what Zeynep is doing, by making her “excellent points about speed, networks that emerge and operate through online media, and the fact that some things (like “it’s good to have friends in high places”) stay the same”?

Those very points, it seems to me, are what we need to discuss if we want to discuss change. Anyone who wants to offer an account of what is new in the current situation will focus on the sources of those changes, and that focus may well be required to answer your subsequent questions.

You ask, for example, about the fact that “tens of thousands of people all around the world actually care enough to follow distant events?” One sociological answer, following Duncan Watts’ work on social ‘distance’, suggests that people do not in general follow distant events, so that the question might be “Why did _this_ event not feel distant?”

But if you ask that question, you are back to media and novelty, and, in particular, to Zeynep’s earlier observations about how present a twitter stream feels, so that it feels odd to read news of tear gas in Tahrir and then someone’s observation about a new restaurant. This sort of juxtaposition happens in newspapers all the time, but doesn’t feel odd the way it does in twitter. But you’d have to discuss why that is, which is to say discuss the difference between older and newer media, even to answer your question about distant events.

My response to your overall observation is “Sometimes, if you want to talk about a political situation, you have to talk about media — Who knew what when, and how? And sometimes, when you want to talk about what’s _new_ in a political situation, you have to talk about what’s _new_ in media. How has what people say and know changed?”

And sometimes you have to do this to get at the bottom of other, related questions, like what makes an event like the current Tahrir uprisings not seem so distant.

Thanks for this, Clay. As you note, I am writing about a particular transition here. I am not sure what anyone would get out of it if I wrote 10 pages about how “it’s good to have friends in high places.” I try to note such obvious, well-understood facts and, instead, try to understand, well, what happens if you can reach your friends in high places using a new kind of medium such as Twitter, and coordinate how you contact, say, the embassy in two separate countries using social media.

Clay writes: “Sometimes, if you want to talk about a political situation, you have to talk about media — Who knew what when, and how? And sometimes, when you want to talk about what’s _new_ in a political situation, you have to talk about what’s _new_ in media. How has what people say and know changed?”

Here I am in agreement, but the debate is about the boundedness of “sometimes.” Specifically if the goal is to understand causality, the entire question is which times do we need to talk about what?

Social science has a tough time with causality.

First, it must attempt to overcome the lack of real experiments, as Zeynep mentions. For large-N research, substitution of old for new media practices can be one variable among many, and some sense of partial causality can be claimed with precisely stated confidence. With few cases, we are left to argue causality and gather suggestive evidence. Comparative case studies can propose accounts of what happens with or without a given factor (say social media), but they are vulnerable to serious flaws from selection bias.

The second problem is more fundamental, in my view. Social events will rarely have a discrete single cause, so muti-causal models are necessary for understanding. If you have sequential causality as the question (i.e. what factors A, B, C, … N caused condition Alpha), then the question becomes both what caused the event and what caused more of it. A more situational causal model such as the “fuzzy set logic” used by Charles Ragin and recently by Phil Howard allows for a combinatory logic on the “independent variable” side of the equation.

But we’re still left with: Was it more important that Twitter was used here, or was it more important that Mona and Zeynep and others had influential friends (say, “social capital”)? Here is where I think the constant argument over “technology was important” versus “other stuff was important” is a tired false dichotomy.

If we’re focused on tech, however, and case selection is based on technological variables, it is extremely important to consider controls for other factors in the literature on mobilization, movements, elite politics, etc. At least, this is necessary to meet social science standards (such as they are) on causality.

By no means is it bad to tell a story about media, but the debates are about causality and not about whether media use matters. I obviously think it does. To most fully tell a single-case story, though, a wider variety of “if not for X could Y result” counterfactuals need to be considered to pacify skeptics about any one claimed cause.

Graham says: “First, it must attempt to overcome the lack of real experiments, as Zeynep mentions. For large-N research, substitution of old for new media practices can be one variable among many, and some sense of partial causality can be claimed with precisely stated confidence.” — Well, no, not really. There is no “old” unmodified by the new anymore. Old and new coexist in a new reconfiguration. No easy way to compare them.

Also, Graham says: “: Was it more important that Twitter was used here, or was it more important that Mona and Zeynep and others had influential friends (say, “social capital”)?” I don’t think this is a well-formed question. Neither my nor Mona’s social capital can be independently assessed without taking into account our activities on Twitter. A better question, imo, is: “how does the formation of social capital work in today’s world and how does social media interact with social capital formation?”

Third, I wrote about this case not to tell a story only about media but a particular case which illuminates how new pathways of connectivity alter dynamics in an age-old question: what determines how an authoritarian regime treats a particular dissident? In this case, a somewhat famous one. I think Zainab Al-Khawaja’s case which broke right after this one is also fascinating (@angryarabiya on Twitter). Hope I can find a moment to write about it.

You’ll note I went to some length to explain some of the classic problems people not familiar with this kind of human rights work might not understand (the different threats posed by the low-level functionary, for example, versus the knowledgeable authorities).

All of these points are well-taken, and I think we’re broadly in agreement. I think the best way to clarify the point at which we differ is to address the question of “why causality?”

I find little objectionable about the original post here, something I’ve tried to make clear. My initial questions were motivated by a desire to explore why it is that some people object to social media–centered account of political events and to what extent those objections might be minimized by a shift in rhetoric to one in which multiple explanations are considered and their relative weights are explained.

In essence, my remaining question is: If there is no such comparison as new and old, how can the emphasis in an explanation center on the new? I would argue that a changed “media environment” could be discussed. Consider two time points, 1990 and 2010: In 1990, there were newspapers and televisions and telephones, and satellites were coming into more common commercial use. In 2010, all these existed but had changed over time in terms of reach, modes of use, and core characteristics. Meanwhile, new technologies were added to the mix, among them widespread mobile phone use and Twitter—both obviously critical for #FreeMona. What is the problem with saying the media environment might be a factor and that it had different states at different times?

As for the question of social capital formation being related to media, I agree that these questions are inextricable at the deepest level. For causal reasoning, however, phenomena need to be delineated and their relationships need to be described in order to make more explicit the model-creation that occurs in our minds anyway. Without some delineation of potential explanations, the question of what “determines” a particular outcome becomes simply a description of events as recorded.

Description is great, and it’s often more illuminating than the competition of models made of variables or of existing social theories. But when it comes to causality, description alone loses its teeth logically, because the potential always exists for gaping holes in the narrative. Historical methodology deals with this by less systematic evaluation of competing explanations and the continuing process of bringing new sources to bear. Social science is based on the idea that a formal situation (such as “treatment of a dissident by authoritarian regime”) can serve as a framework to compare cases. If the dissident situation can be abstracted, why can’t the multiple explanations?

In sum, I’d like to learn more about how you conceptualize networked causality, and I apologize if you’ve written volumes about this that I’ve completely missed. But at root I really wonder if causality need be the goal. As before, thanks for a great discussion.

I think we’re missing one simple, fundamental piece of critical information in the flow here, which is the contact of the US Embassy. In the current political situation in Egypt, it is probably reasonable to assume that concerted pressure from the Embassy contributed to the speed of Mona’s release.

Had she not tweeted herself, and had their not been a flood of calls to the Embassy, I’m almost certain this direct pressure would not have been exerted so rapidly.

Thus, it’s not about Twitter, it’s about the content getting out to the right audience in a timely manner. What Twitter does is shorten that cycle. Could it have happened without social media? Sure, but it would have taken much longer.

Brett King

Author – BANK 2.0

How can it also not be about Twitter if, as you say “Twitter shortens that cycle”. That’s exactly my point. Faster is different.

Hey Zeynep –

Saw your excellent blog post and wanted to add some comments based on my experience ….

“Most important conceptual point is this: The idea that “social media does help make X happen” DOES NOT mean it was just social media–because that is a theoretical stance which views social media as not part of this word. In fact, critics of social media often fall into this trap as they keep repeating “it wasn’t just social media” as if that were a valid criticism. To state “it wasn’t just social media” is a mere and trivial description of the world, not an analysis of dynamics of how social media plays a role – was it big or small? Was it crucial or trivial? What were the pathways?”

Here I think you can draw an important lesson from the “failure” of the Stanford-led research on the effects of television on children. At an ICA conference, Steven Chaffee admitted to me in a private conversation near the end of his life that the researchers asked the wrong question: They asked, “Did television affect children?”

After years of research, social scientists presented their final conclusions on the question “Does television affect children?” Their answer: Some children; in some conditions; some of the time.

Chaffee said that in his experience after decades of work was that his Stanford colleagues and others had asked the wrong question. The research question should have been: How does television affect children?

As it turns out, the methods of social science require this ambiguous answer. The naive question of “Does?” cannot be answered by social science as social science methods cannot establish this kind of causality. As another Stanford researcher said, “There are just too many intervening variables to establish scientific causality.”

As you say: “Good analysis in social science also requires good theoretical understanding which basically means correctly conceptualizing the dynamics in play. Start wrong, and you aren’t going anywhere.”

Or put more succinctly: If you ask the wrong question, the answer doesn’t matter

This mistaken framing of the question in the field of children and mass media research , as you point out in your post, is the same one as the question “Did social media cause x?”

To sum up, the proper research question is: “How does social media make x happen?” and not “Does social media make x happen?”

Completely agreed. I have seen so many serious people claim that Television doesn’t impact everyone. For me, such statements don’t even pass the laugh test. What they mean is that there are no methods by which we can conclusively measure the precise impact of television on every single person and separate that impact from every other factor out there.

Excellent discussion as usual that explains a lot.

You say that there is no way to scientifically set up an experiment in the social sciences (artificially anyway) in order to test hypotheses, but it must surely be the case that history or events sometimes offer us controlled/semi-controlled experiments – not on purpose, of course, but that they just happen.

In this sense, it must be possible to compare and contrast different situations in which :

1) Person is arrested, brought to police – with NO notoriety and NO connections

2) Person is arrested, brought to police – WITH notoriety but NO connections

3) Person is arrested, brought to police – with NO notoriety but WITH connections

4) Person is arrested, brought to police – WITH notoriety and WITH connections

– and what their respective outcomes are.

And by “connections”, I mean not just connections to powerful people, but powerful people who actually are in a position to put pressure on the particular police/military forces detaining an individual, either diplomatically, or otherwise.

I believe in the power of social media and agree with just about everything you say here, but I suspect that Mona’s notoriety and connections to the State Department had more to do with her actual timely (fortunately) release than did the social media surrounding the event. That is to say, the fact that someone probably well placed to put pressure on Cairo was contacted and the word was spread was secondary to the fact that this person (Embassy, etc., or persons) were actually able to put pressure on Cairo in the first place – and the fact that the police forces (or govt, or what have you) reasonably expected to pay a price for their behavior.

“5- Social media works for prominent people better”

There is also the corollary that it will work better not only for prominent people, but moreover that prominent people who are Tweeting or writing about such incidents will also receive more attention. i.e., if there were not people like you writing about it, the reaction (if there was one) from the Embassy, or State would have been more tepid or nonexistent.

How many other people are languishing in prisons around the world that we don’t hear a peep about? Lots.

Problem with this is:

1) Person is arrested, brought to police – with NO notoriety and NO connections

2) Person is arrested, brought to police – WITH notoriety but NO connections

3) Person is arrested, brought to police – with NO notoriety but WITH connections

4) Person is arrested, brought to police – WITH notoriety and WITH connections

– and what their respective outcomes are.

To do establish conclusive causality, you need the same person, same police with and without notoriety and with and without connections. Back to the no alternate universe, no time machine, no cloning technology problem. Yes, comparative work is VERY helpful but it is not conclusive in the sense someone can always point to an intervening variable which makes a difference besides the ones you are interested in.

And for this sentence: “but I suspect that Mona’s notoriety and connections to the State Department had more to do with her actual timely (fortunately) release than did the social media surrounding the event.”

My claim is there is no separating the “social media surrounding the event” from “Mona’s notoriety and connections to the State Department.” Her notoriety is completely intertwined with social media and the way State Department acts is not independent of the campaign, etc. It is all one big mix. I cannot answer “which of these was more important” because the “these” are not separable.

Agree with your corollary to the degree I understood it correctly.

Yep, there are many people languishing in prisons without a peer. I hope to write more but this kind of “protection” of sorts we are witnessing for a few “micro-celeb” activists is, almost by definition, going to somewhat protect only a few people because the whole point is that they can garner a lot of attention in short period of time. It’s simply not going to work for large numbers of people all at once. While it is still pretty significant that such a class of people have emerged; by no means is it even remotely sufficient.

“Yes, comparative work is VERY helpful but it is not conclusive in the sense someone can always point to an intervening variable which makes a difference besides the ones you are interested in.”

– Sure, yes. Thanks.

” My claim is there is no separating the “social media surrounding the event” from “Mona’s notoriety and connections to the State Department.” ”

– Yes, but they are clearly two different concepts/ideas which we can sort out mentally and talk about, even if there is no real precise way of measuring them. It is still possible to ask the question. It is possible to envisage vibrant and active “social media surrounding the event” without any State Dept of official involvement, and with no action being taken whatsoever to remedy the situation. I guess what I am trying to say is that social connectedness (whichever ways you have of measuring this) or “celebrity” status does not necessarily mean : power to change one’s situation, or destiny, necessarily.

I understand better your point though, that with complicated networks like this it is extremely difficult, even impossible to totally isolate any one aspect, as they are all interacting simultaneously and all affect one another.

As for the broader question “Do social media tools affect social movements”, I agree that it is a pretty meaningless question – of course they do.

Graham, we are obviously mostly in agreement.

Let me say, first, that I don’t think Zeynep is trafficking in the kind of mono-causal treatment of social media that could be reduced to one end of the ‘tired false dichotomy.’ What I think she is doing instead is saying “Lets look at how the changed media environment might affect changed outcomes.”

I also think you’d be surprised at the amount of concern-trolling in these conversations, where factor Y is introduced into a conversation about X not as a way of balancing the conversation, but as a way of changing the subject. As @SarahKendzior recently said on Twitter, “Zeynep’s right — if you study the net, you’re fine. If you study the net’s impact on politics, society, etc., you have a problem.”

You also say “But we’re still left with: Was it more important that Twitter was used here, or was it more important that Mona and Zeynep and others had influential friends (say, “social capital”)?” Here is one of the few places where we disagree. I don’t think you can frame ‘techno-determinism vs. social constructivism’ as a tired dichotomy and also want a weighted accounting of these kinds of concepts, _because media is one source of transmission for social capital._

Not only are social events not mono-causal, in other words, the causes aren’t even separable or renderable in any orthogonal way. As Bruno Latour is fond of asking “In which building is ‘social capital’ produced?” There is no way to adjudicate the question you are asking above, if social media alters the way social capital is traced and acted on.

New technologies make new outcomes possible (anything that fails to do that either isn’t technology or it isn’t new), *and* tools are used by people. Like a Nekker cube, you can look at the way networks of people approach new problems, with the tools included in the narrative as a means of effecting certain outcomes, or you can look at the way tools alter the way networks of people get things done. However, also like a Nekker cube, you will never be able to make one or the other of these narratives finally express itself as the really real one.

As you note, Clay, we are broadly in agreement on this. I agree that Zeynep’s account was not mono-causal; it was explicitly concerned with the complexity of the matter. As I’ve noted above, I do think there is a question of emphasis.

The reason I noted the “tired false dichotomy” was that, despite all discussions, we still have people behaving as techno-enthusiasts and techno-skeptics. I’m in an odd position here, because I think technology is extremely important, but I often feel scholars and journalists on this question lose some force by making tech the center of a given story.

Clay said: “I don’t think you can frame ‘techno-determinism vs. social constructivism’ as a tired dichotomy and also want a weighted accounting of these kinds of concepts, _because media is one source of transmission for social capital._”

Here, I have to say this is a mischaracterization of my argument. As I put it originally, I was talking about people arguing about one thing being “important” in a narrative. This is because I think determinism and causality are specific problems of their own, and the argument was about emphasis. So, it’s true that someone who thinks technological determinism and social constructivism could not occur at once would fail to account for the role of technology in social processes; I just didn’t claim that.

So, in essence I think we come out even more in agreement, if not having resolved the question of tactics regarding discussion of technology’s importance in the context of social and political processes. We can be thankful, at least, that blogging technology affords us the opportunity to discuss such things over a holiday weekend and without ever having met, and that we’ve chosen to avail ourselves of this affordance.

Pingback: How Twitter helped rescue Mona El Tahawy — Tech News and Analysis

Pingback: gli spezzati e i salvati | Alaska

Pingback: Too much information: links for week ending 2 December 2011 | The Barefoot Technologist

Pingback: Reporting on Conflict | Peacemakers Trust Media Watch Blog » A New Theory for the Foreign Policy Frontier: Collaborative Power

Pingback: A New Theory for the Foreign Policy Frontier: Collaborative Power » OccupyEverywhere.ca

Pingback: Occupy Wall Street Mockupation: reality gets weirder (and faster) all the time | civilized disobedience

Pingback: Ming Holden: Kenya Dispatch: The End of Structure | News Fresh Daily

Pingback: Jillian C. York » Do solidarity campaigns really help bloggers?

Pingback: Do solidarity campaigns really help bloggers?

Pingback: Ming Holden: Blogs Never Promised You a Rose Garden | Le monde de l'information

Pingback: Social media and equality | lcmediapowerpolitics

Pingback: Exercising Leadership in the Digital Age | luearaujo.com

Pingback: Social Media and the Arab Spring « Speak to the Left Hand: A Lefty's Perspective

Pingback: WikiLeaks, The Arab Spring and the Whole Ball of String | thepointybit

Pingback: Learning a lot about what you already know. Vol. “Arab Spring and Social Media” | two cents from lentz

Pingback: Cyber-realism, Oxymoron or plain contradiction? | Mariana Filgueira Risso

Pingback: Social Media and Social Change: Learnings from the Arab Spring | saadiazahidi

Pingback: Of Springs, Protests and Social Media. ← Juan Maquieyra